That Time Google Tried to Build a Neighborhood

The New Cities Part I: An Interview with Andrew Miller, former Associate Director of Mobility at Sidewalk Labs

This is part 1 of 5 in Urban Proxima’s series on the theory and practice of building new cities.

Part 1: That Time Google Tried to Build a Neighborhood

Part 2: Outsourcing Sovereignty

Part 3: Urbanism-as-a-Service

Part 4: Urban Larping

Bonus: Dreaming of Atlantis

The following is an interview with Andrew Miller, author of the urbanist Substack Changing Lanes and co-author of the forthcoming book The End of Driving: Automated Cars, Sharing Vs Owning, and the Future of Mobility.

In today’s conversation, Andrew and I discuss his time spent at former Google subsidiary (or as they put it, an “Alphabet company”) Sidewalk Labs, the company’s ultimately-unsuccessful attempt to build a neighborhood from scratch, and the lessons learned along the way.

The road to Sidewalk Labs

Jeff Fong: Hey Andrew, can you start by telling us a bit about your professional background?

Andrew Miller: My professional background is eclectic. I started out training to be a historian, of all things, specializing in the history of First Nations / American Indian peoples from pre-contact to the end of the nineteenth century, particularly those who interacted with both French and English colonists. I studied at McGill, then Yale, and finally Johns Hopkins for my doctoral degree; but by the time I'd earned it, I knew I no longer wanted to be a professional academic.

Urban transport had always been a hobby of mine. I distinctly remember one morning, before driving up the highway to the campus where I was teaching a course on British history, receiving a circular in the mail about an upcoming bus rapid-transit project in my neighbourhood, and thinking, "in my next life, I'd like to work on stuff like this". My next thought was "actually you only get one life".

A few months later I was working at the Ontario Ministry of Infrastructure.

I spent the first year learning the ropes and pestering my boss to let me work on the transit file. Eventually I was permitted to, and almost immediately thereafter transit became a matter of strong political salience. I rode that wave, going from making up/down recommendations on whether to fund particular transit projects; to overseeing the entire +$2B provincial transport budget; to doing special projects for the Ministry of Transport; to running Ontario's Municipal Transit Policy office.

After that I spent four years leading and championing a project for a new rapid-transit expansion in Mississauga (Toronto's western suburb and Canada's sixth-largest city).

JF: And how did you end up at (Google's) Sidewalk Labs?

AM: As that project was wrapping up, I had to decide what to do next, so it was good for me that Sidewalk Labs (SWL) came calling.

I had been excited when their Toronto project first came to town, and I sent over a resume cold, heard nothing, and forgot about it. Then, months later, they contacted me to inquire if I'd be interested in working on mobility projects for them. I was interested, and soon I came on board; my first day was just after the new Toronto office opened.

The Sidewalk Labs mission

JF: When you joined, what was the original plan?

AM: SWL started as a pet project of Larry Page, co-founder of Google and then-CEO. He was convinced that cities had lots of heretofore-intractable problems, but the advent of the Internet allowed opportunities to solve or ameliorate them, and wanted an organization that would try to do so. So he co-founded SWL with Dan Doctoroff, former Deputy Mayor of New York City, to do just this.

The first couple of years was just ideation of all the things one might do, all of which got written down in a book called Building a City from the Internet Up. The next step was to find an opportunity to implement these ideas.

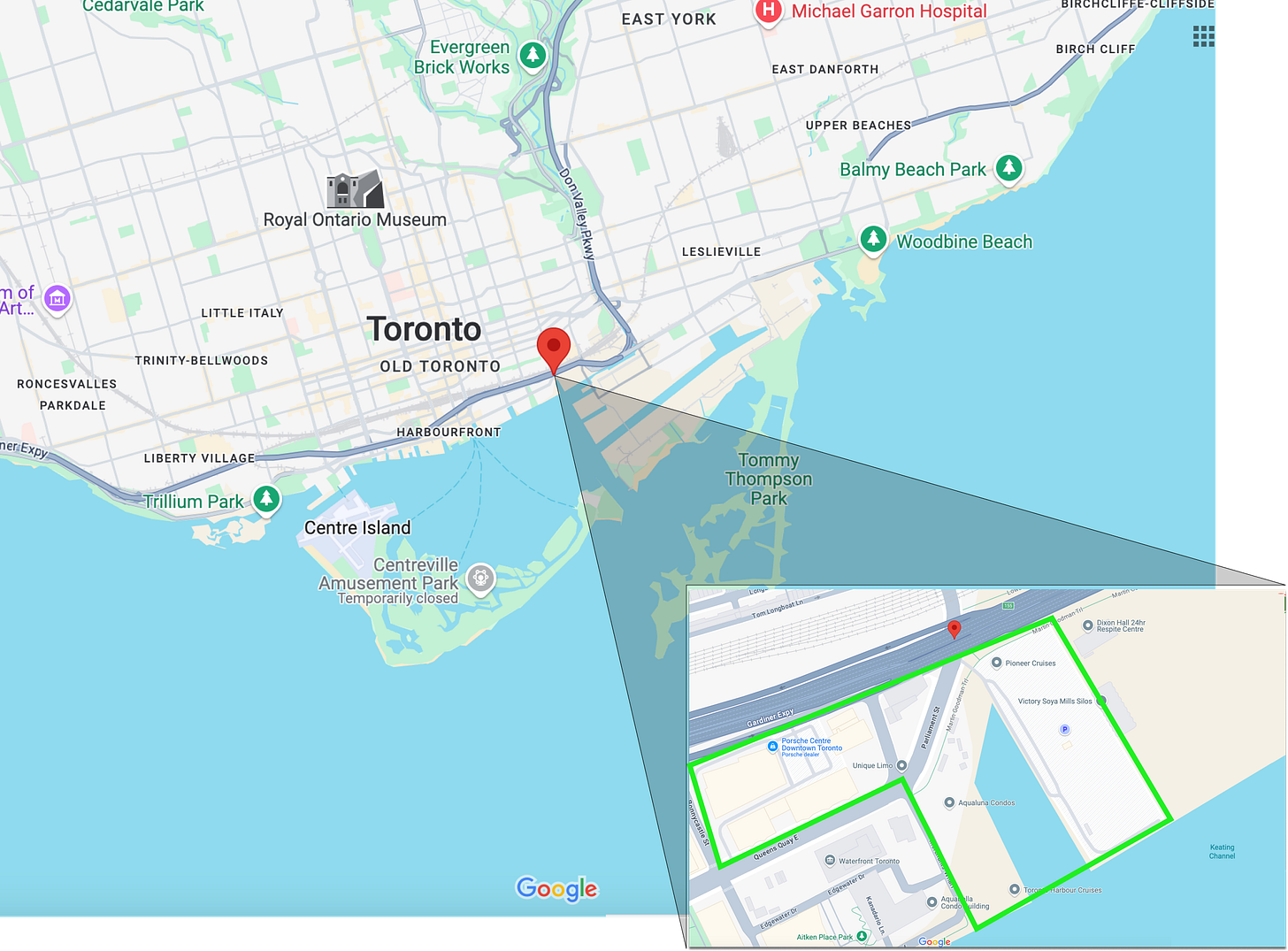

Lots of cities around the world called, encouraging SWL to come to them and do a pilot, but it was Toronto that caught SWL's eye. This was for two reasons: firstly, Toronto had (still has) a large chunk of undeveloped, former-industrial land in the downtown, right on the lakefront, just a few kilometres from the central business district, and so the economic capital of the whole country.

Secondly, the development agency responsible, Waterfront Toronto, was explicitly looking for a partner to help develop this land, called Quayside, and had issued a Request for Proposals to do just this. So in SWL's eyes, they had an unparalleled opportunity, and a partner that was ready and willing to work with them. And, crucially, the opportunity was not to build a new city; it was to build a new neighbourhood.

One can't just point at a farmer's field and whistle up a city. There are economic forces which determine whether a city will flourish or not. But Toronto is already a city, so what SWL was building wouldn't need to stand on its own, it could slot into the existing structure. So they competed, and won, and set out to write a plan, in detail, of what SWL would build.

The original plan was threefold: vertical development, horizontal development, and product design.

Vertical development was traditional real-estate work: buy this land, build on it, and resell it, or access to it: condo sales, rental of shops or apartments, and so forth.

Horizontal development was building the underlying infrastructure: district heating and cooling, improved wastewater, green power, and so forth, which SWL would build and then get availability payments from the city for providing.

Product design was building all sorts of urban tech amenities—smart parking sensors, smart thermostats, more—prototyping and proving they worked, and then selling them to interested parties.

JF: What parts of the project did you end up working on?

AM: My role was to lead the mobility file for the project. This had a lot of features, but the principal goal was to build a consensus around transit service for Quayside. SWL believed, correctly in my view, that the sort of neighbourhood they wanted to build needed to be firmly embedded in the city's existing rapid-transit network.

Then (and now) there was only sad, low-frequency buses serving the site, and much more was required. The obvious candidate was light-rail transit (LRT), connecting the site to the commuter-rail-and-subway-hub a few klicks away. As someone who had just planned a whole new bus rapid-transit line (BRT) in the area, my job was to help get the LRT to the same place. There had been talk for years of a Waterfront East LRT but it was still conceptual and no one's priority. My job was to refine the plan, advance it, lobby for it, and do whatever it took to get it built.

Along the way, I was planning for automated-driving infrastructure, figuring out how bikeshare and scootershare would work, right-sizing bike storage, working out bus-service patterns, evaluating start-ups to partner with, and all sorts of mobility-related things, as one does at a start-up. But the primary job was getting everyone to think that SWL had the right ideas on urban mobility; and their best idea was that Toronto needed better rapid transit to serve its waterfront.

JF: The horizontal and vertical design portions sound like straightforward real estate development to me, but the product design piece strikes me as extremely Silicon Valley.

AM: Yes, the product design piece was pure Silicon Valley, while the vertical development piece was classic real-estate development. The firm did regard itself as a meeting between technologists and urbanists, so naturally it combined aims and methods from both.

JF: Within the product design work stream, what was SWL trying to build that they thought was missing from (or too difficult to add to) existing developments?

AM: There were some fun gadgets, like better smart thermostats, that were on the table; another one that I quite liked was Pebble, a sensor one could embed in pavement that let one know if a parking spot was being used. The advantage there, as I recall, was that the cost was 100X cheaper than anything on the market; at that price one could put them everywhere, and really start developing markets in parking, street and otherwise.

But those were less important than the infrastructure-level innovations. As such, they would be impossible to retrofit, or so expensive as to be practically impossible. District energy, for one. District heating and cooling using the wastewater system as a place to capture or shunt heat, for another. Heating systems in pavement that could prevent ice from forming, linked with computer systems to manage operations efficiently. Buildings with thoughtful tool libraries and storage to be accessed digitally, so apartment-dwellers wouldn't need to keep as much stuff in their living spaces. Buildings where interior walls could be rearranged relatively painlessly, to facilitate businesses growing or shrinking their footprint. And so on.

The biggest single innovation was 'tall timber'; modular building construction from wood and steel, without concrete, done as much as possible from within factories, to enable fast, cheap, sustainable construction. It's still a good idea and I'm glad other firms have continued to pursue it.

JF: What specific problems were they trying to solve? And who did they think they were trying to solve them for?

AM: There was no specific problem being solved so much as identifying all the pain points of urban living: utilities are too expensive, living in a small space is too uncomfortable, the weather makes it unpleasant to go outside, travel within the city is too expensive or difficult. And the reason to solve it is to make city-dwelling simultaneously more affordable and more comfortable, so more people would want to do it.

Fundamentally, everyone involved loved cities, and wanted the benefits of city living to be accessible and enjoyable for everyone, especially those who are often locked out of it: families, the elderly, and immigrants.

Planning to (attempted) execution

JF: What actually ended up getting built?

AM: Nothing. The project ended before the firm built anything.

Why did the project end? Dan Doctoroff, the former CEO, explained it all on a podcast.1 Partially this was because of the Covid pandemic, which threw commercial real-estate markets into turmoil. Partially it was because SWL had a weak counterparty in Waterfront Toronto.

SWL had already agreed upon a price for the land they wanted to develop, but given how much risk the pandemic was creating, SWL went back to renegotiate the deal. And Waterfront refused to do so. I have no insight into any of those negotiations, so I don't know why they refused, but I imagine the steady flow of bad press that had surrounded the project had something to do with it.

With the flagship project dead, I left SWL, so what happened after that I have no specific knowledge of. Without a real-estate project, all that remained in any case were the spinoff innovations; these stood on their own for a while under the SWL brand, before they (and the brand) were absorbed into Google. I think Google chose not to pursue these, though I'm not sure. I think some of the software pieces were integrated into Google Earth.

JF: Were there any assumptions at the beginning of the project that turned out to be wrong? What did SWL misunderstand about cities?

AM: There were many incorrect assumptions! But the biggest one, I think, was 'a city government is a good client for a start-up'.

As it turns out, city governments are terrible clients. In no particular order:

Limited budgets

Diffusion of responsibility: not only is there a Mayor, and individual elected councillors, but there are also appointed department heads, and the leads of separate agencies (fire, police, transit, more)

So getting anything done involves lots of meetings, persuasion, and friction

And there are innumerable veto points

Extreme risk aversion

Highly detailed, slow procurement processes

To name only a few. A start-up, even one capitalized by Alphabet, is taking its life into its hands by going to a city government for revenue. However much any one actor in the system says they want innovation, the system as a whole will be slow, stingy, unwilling to tolerate risk, and already captured by dominant players.

And this was fatal to the whole project. SWL was right to think that innovation can solve many city problems; but wrong to think that cities want to solve them. Or rather, that they want to solve them more than they want to avoid doing anything risky; or to avoid being blamed if a solution fails.

There was a play written about SWL's attempt to build a smart city in Toronto. It's fiction, but the playwright did his homework. Towards the end, he has his fictionalized version of Dan Doctoroff, frustrated that he can't get the smart-city plan approved, say this (emphasis mine):

“It's funny. I've tried for two years to figure out which room I should be in to get what I want. You know what? There is no room. There is no person or group of people I can persuade. Power here is so spread around, so diffuse, it's like people want to pretend it doesn't exist. Even the people who have power pretend they don't. I used to think that was cultural, that there's some kind of Canadian reticence that makes power invisible here. But it's not Canadianness. It's not politeness to a stupefying fault. It's because power kept out of sight is also kept out of mind. If the power isn't evident, then no one can get too upset when it's used. It's a frictionless way of getting your way. It's intentional. The political structures here ruthlessly serve the maintenance of the status quo.”

This is an indictment of Toronto, certainly. But to some extent it's an indictment of almost all city governments. If I was a start-up, I wouldn't build a business where all my clients were like this.

JF: Was there anything that you found personally surprising? Any expectations you had or previously held beliefs you ended up changing?

AM: I had an expectation that Toronto would be excited about doing something bold, and different, that would make the future better than the past. Consequently, I was crushed at how easy it was for a small combination of resentful competitors, fame-seeking activists, and comfortable, virtue-signalling progressives to keep the city firmly stuck in the status quo.

I now regard SWL's failure to build a 'city of the future', or rather a neighbourhood of the future, as another example of the larger problem of North American stasis. It's part of our larger failure to build abundant housing, or high-speed rail, or adequate rapid transit, or nuclear power plants, or high-capacity power grids, and on and on.

As

has noted: In America, you can do anything you want as long as no one is inconvenienced, no one can get hurt, and no one can lose their job. People may not like the status quo, but for any given change, there's a majority that would benefit a little, and a small group that would be worse off. The latter pushes back hard to defend their interests, and the former doesn't resist, because they are insufficiently motivated to do so. And so everything worsens.For the issues I care about—climate change, urbanism, road safety, and productivity and economic growth—we're stuck in a bad equilibrium. The YIMBYs give me hope, in that they've shown how relentlessly advocating for their ideas has begun to make that majority resist more.

I intend to follow their example: Changing Lanes is my relentless advocacy for progress and abundance in mobility.

JF: Well, thank you for taking the time to give the backstory on this Sidewalk Labs project. It is as fascinating as it is, unfortunately, unsurprising.

Postscript

Walking away from this conversation, I had two reactions: one as a Yimby activist and the other as a Product person.

The Yimby reformer in me is completely unsurprised that working with a municipal government felt like trying to strangle smoke. Political institutions are organic things and in much the same way that humans are sort of an evolutionary least common denominator, municipal institutions are often the way they are because that’s the easiest way for them to be. Path dependency is a hell of a drug.

Where the Yimby and the Product person in me start to shake hands, though, is in where I think that you can overcome that institutional inertia.

Getting a political system to do something it’s not built to do (or, more foundationally, changing the way it works) requires a lot of external force. There needs to be a problem painful enough to create raw political energy in favor of change; and, critically, there has to be a someone ready to harness that political energy and use it to deliver the policy for which there’s pent up demand. I think that partially explains why Serve Robotics actually succeeded in getting permission to rollout sidewalk-based delivery drones in places like Los Angeles (their GR team deftly navigated some specific political currents). But perhaps getting a municipal government to create a permission structure for new technology (i.e. to agree to not stop you) is just different from getting the same to be an active partner in doing something new (more like what SWL needed with the Quayside project).

Regardless, the political energy never materialized for SWL and things got bogged down in the risk averse proceduralism of the city’s government.

Given all the challenges SWL faced in Toronto (and other technologists and policy reformers have faced in cities across the world), it’s no surprise that some folks have thought about starting over from scratch. That’s the topic we’ll continue exploring through the rest of this series, picking up with city building as economic development.

Tune in next time for a deep dive into charter cities, startup cities, and something called competitive governance. In the meantime, let us know what you thought about the interview down in the comments.