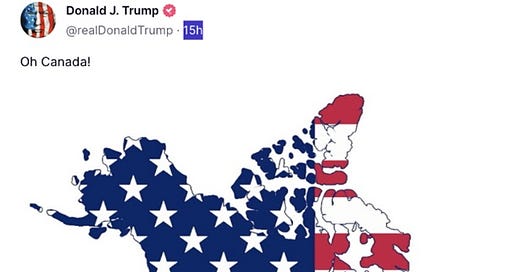

The proposed annexation of Canada is in the news.

I’m publishing this piece on 15 January 2025, which means the second inauguration of Donald Trump as President of the USA is less than a week away. He’s made many claims about what he wants to achieve with his administration. Regarding Canada, he’s made two big ones.

The first was that he will impose 25% t…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Changing Lanes to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.