The Cruise Shutdown Is Bad News for Tesla

Making cars and operating robotaxis are very different things

The big development in the robotaxi world this week is a sad one: General Motors announced on Tuesday that it would no longer fund Cruise. That means that GM is ending its bid to compete in the robotaxi market.

The first thing to say is that I have great sympathy for the Cruise team. Aside from the professional uncertainty that an announcement like this generates, I am sure they are gravely disappointed by the end of Cruise’s ambitions to bring affordable robotaxis to the cities of the world. Changing Lanes has readers at Cruise: I extend my condolences to them.

GM's retreat is not only a setback for the sector, but also an important data point in our thinking about what it will take for any robotaxi firm to succeed. Here are two propositions I have advanced before, and one new one:

Traditional automakers are poorly equipped to run a robotaxi business; the two business models are antagonistic, not synergized

Good relationships with regulators are paramount to success…

…and so is access to top AI talent

I think the dissolution of Cruise supports all three propositions. And those propositions lead to the same conclusion, which I also have advanced before: Tesla’s ambitions in robotaxi will fall short.

Before we get into that analysis, though, let’s take a moment to review Cruise’s promising beginnings and unfortunate end.

The Rise and Fall of Cruise

Cruise's story began only a decade or so ago in 2013, when Kyle Vogt founded the company to develop self-driving technology. Within three years, Cruise had made enough progress to attract GM's attention, leading to a $1 billion acquisition in 2016. At the time, this seemed a prescient move by GM CEO Mary Barra; a strong move by a traditional automaker to compete with tech giants like Google in the development of automated driving.

Under GM's ownership, Cruise moved fast and aggressively. Waymo, Google’s automated-driving spinoff and Cruise’s principal competitor, had spent years testing in controlled environments before gradually expanding to public roads. Cruise pursued a different strategy, aiming to rapidly scale its service in dense, uncontrolled, complex urban environments. Its fast moves attracted billions in additional investment from firms like Microsoft, Honda, and SoftBank; at its peak, its valuation was $30 billion. By 2022, Cruise was testing vehicles in San Francisco and preparing for nationwide deployment. This rapid growth no doubt impressed GM and its other investors, but didn’t come cheap: Cruise lost $3.5 billion in 2023 alone.

Had it been able to sustain its forward momentum, these immense sunk costs might ultimately have been recouped. But it was not to be; the firm’s aspirations ultimately foundered on the events of one bad evening.

Cruise robotaxis. Image courtesy of Cruise

On 2 October 2023, a jaywalker stepped into a San Francisco street, beginning a series of events that would lead to the firm’s demise:

A human driver who had stolen a car and was driving it recklessly struck the pedestrian. This driver was not apprehended and remains at large

The pedestrian was thrown into the path of a Cruise vehicle, which struck her and trapped her beneath the car

The Cruise vehicle, lacking undercarriage sensors, was ‘unaware’ of the pedestrian’s presence, and proceed automatically to park at the roadside, dragging the pedestrian 6 metres (20 feet) at a speed of 7 mph

Crucially, Cruise informed the overseeing regulator of the collision, but not the dragging; the regulator remained unaware for another 15 days

Cruise’s handling of the incident, which Cruise itself describes as “submitting a false report”, led California regulators to revoke the firm’s permit to operate driverless vehicles in the state. The consequences were vast: Cruise was forced to pause commercial operations everywhere; CEO Vogt resigned; and the firm was forced to lay off employees and cancel its development of a custom vehicle. While the firm had announced plans to return to testing in San Francisco with safety drivers aboard, this week’s announcement means that will not happen.

Cruise's sudden downfall highlights a fundamental truth about the robotaxi industry: traditional automakers are poorly equipped for it.

The Business Model Disconnect

GM’s plan for Cruise is to absorb its technology and (some of its) talent into its core business. GM already had an internal programme to develop advanced driver-assist features (ADAS)— think smart lane keeping, cruise control, automatic lane changes, and such—called, confusingly, ‘Super Cruise’. Cruise’s technology will now be folded into Super Cruise; the strategy will be to build a better ADAS, not an automated driving system (ADS) that can replace a human driver.

GM’s move here mirrors what we’ve seen in recent years from other big automakers. Ford and Volkswagen had a joint venture to develop fully-automated vehicles, Argo AI; they closed it in 2022. Hyundai had its own firm aspiring to a robotaxi service, Motional: just this fall, as Tim Lee notes, Motional’s CEO stepped down and Hyundai made a deal to provide Waymo with vehicles for the latter’s self-driving software. I agree with Tim that Motional’s days seem to be numbered.

The conclusion is inescapable: building cars and running a robotaxi service are antithetical exercises.

That’s because the two activities share so little common ground. Car manufacturing is about running efficient, optimized supply chains, assembly lines, and dealer networks. Running a taxi service involves fleet management, dispatch software, customer service, and most crucially, maintaining constant uptime in a variety of complex urban environments. CEO Barra drew the distinction bluntly in her announcement that GM would no longer fund Cruise: "You've got to really understand the cost of running a robotaxi fleet, which is not our core business".

Kyle Vogt, founder and ex-CEO of Cruise, and Elon Musk, CEO of Tesla Motors, posting on X shortly after the GM announcement

The only synergy one can imagine between the two sectors is the vehicle. A robotaxi service that uses a custom vehicle design to provide better service might be one that benefits from being part of a vehicle manufacturing concern, to ensure it doesn’t have to rely on external partners for its fleet. But Cruise abandoned plans to do this: its custom robotaxi, the Origin, was cancelled earlier this year.

So what sort of parent company does a successful robotaxi firm need? To answer that, let’s look to the firms that remain the leaders in the American robotaxi field: Waymo, backed by Alphabet; and Zoox, backed by Amazon. What do these companies have in common?

Firstly, they are digital companies with substantial experience in software development. This is important, but set it aside for now.

Secondly, they are more-or-less monopolies in their fields, giving them substantial financial room to support moonshot ventures. Few firms can take on expensive, risky initiatives with the potential for significant returns later on, but monopolies can. Also, as monopolists, such firms have, almost by definition, maximized the revenue potential of their own fields; if they want to grow, they must look outside their core competencies to do so.

All of this is important background for any assessment of Tesla’s robotaxi ambitions.

As I’ve written before, Tesla has made bold claims that its move into offering robotaxi service will add “trillions” to its market capitalization. How much weight should we give those predictions?

On the plus side, Tesla is a commercial mass-market car manufacturer.

It will take advantage of that in a few ways. It will indeed build custom vehicles optimized for automated driving: the Cybercab and the Robovan, as per the launch event, will not feature steering wheels. (I note in passing that Zoox is doing the same.) They will indeed seize whatever synergy is available. Even more importantly, Tesla’s vast library of driving data, and the firm’s work to build sophisticated ADAS, should help them to build an effective ADS, though how long that will take remains to be seen.

But on the minus side, Tesla is a commercial mass-market car manufacturer.

Leave aside that nothing in the firm’s history suggests it has the operational expertise to run a large-scale taxi service. Focus instead on the larger problem: like GM and other firms in that space, Tesla has no monopoly. Far from it: it faces increasingly sharp competition in the personal-vehicle market, especially from Chinese companies like BYD. Canada and the USA are imposing tariff walls to keep Chinese electric-vehicles out, but China may be able to compete even carrying such burdens; and North American tariffs won’t help Tesla cars sell in foreign markets.

As I noted at the time, the Tesla robotaxi launch event led to the company’s stock price falling. It’s easy to see why: GM spent $10 billion on Cruise before pulling the plug, while Waymo has raised more than $11 billion to date. Tesla’s annual profits are consistently lower than General Motors, which suggests investors might continue to push back on Tesla’s ambitions in this space; conversely, Tesla’s market capitalization is a staggering 25 times GM’s, which suggests Tesla’s investors are bullish on the future of the company. It certainly seems like Tesla can afford to pursue this business line, at least for now.

But while Tesla's high market valuation gives it some runway to pursue ambitious projects, money alone can’t help it solve its next problem: navigating the complex regulatory landscape, as Cruise was unable to do.

The Regulatory Tightrope

The demise of Cruise stemmed from two failures: one technical, one cultural. The technical failure was the lack of any sensor on the robotaxi undercarriage that could detect a trapped pedestrian. Introducing such a sensor, along with an instruction to the ADS to remain in place if a pedestrian is trapped, is a straightforward solution to the problem. I don’t have any specific insight, but I imagine all companies implemented exactly these changes immediately after Cruise’s public failure to do so. That means that we can (and should!) expect that such an incident will never be repeated.

Given that outcome, that single mistake need not have been the end of Cruise. What was the end of Cruise was its decision to treat regulators as opponents rather than partners.

Contrast this approach with what I’ve called the slow-and-steady approach taken by other firms. Waymo, for instance, has spent nearly 15 years methodically expanding its service, starting with a small pilot in Phoenix before gradually extending to San Francisco and other markets. When incidents occur, Waymo has been consistently transparent and cooperative with regulators. The company provides detailed reporting, participates openly in investigations, and adjusts its operations based on feedback.

So: success requires working with regulators, moving carefully, and maintaining public trust. Tesla's plan to launch robotaxis (in 2025!) seems to me to be on the wrong side of this dynamic.

Tesla’s CEO, Elon Musk, seems poised to wield significant influence in the next Trump administration, which is already yielding dividends; it seems likely that the Department of Transportation will soon issue new federal regulations for automated driving, easing Tesla’s path (as well as the paths of its competitors). It’s important to note that for the most part robotaxis will be regulated at the state level, where national influence will have less value. While California and Arizona have established a clear framework for robotaxi operation, other jurisdictions are less prepared. Kentucky recently tried (and failed) to ban autonomous trucking outright, for instance. As robotaxi companies look to expand beyond their initial markets, they'll need to navigate a patchwork of state and local regulations. This will take patience, time, and delicacy. Musk can be patient. It’s not clear, given the state of the car market, whether he has time. And the less said about his delicacy, the better.

This complex regulatory environment explains why the successful players move so deliberately. A misstep in one jurisdiction can cause harm across many others. In the wake of the Cruise incident, I was told, on background, by insiders at other robotaxi firms that they gave Cruise significant grief for their mishandling of the affair, given the blowback was about to make every firm’s situation harder. Cruise’s demise should underscore the idea that confrontational or aggressive moves in this space will ultimately make the sector as a whole worse off.

The AI Talent War

The demise of Cruise has brought forward a less obvious, but still critical, challenge facing the robotaxi industry: the fierce competition for artificial intelligence talent. If anonymous Redditors are to be believed, part of Cruise’s problem was its inability to keep up with other big tech firms in the contest for AI talent.

Both Google and Tesla believe that artificial intelligence is the key to successful automated driving, and given the incredible leaps that AI has made in the past few years, that seems right. But the unfortunate consequence is that the skills needed to make robotaxis work at scale are the same ones in demand at companies working on large language models, image generation, and other AI applications.

Unfortunately, companies that move atoms rather than bits can’t, and will never, be able to scale fast enough or monopolize markets enough to out-earn purely digital companies. Traditional automakers certainly can’t, meaning that staffing to an appropriate level will be a challenge. As large as Tesla’s market capitalization is, Alphabet’s is almost double; yet the same anonymous Redditors note that even Waymo’s ability to retain staff has been tested by "aggressive penny-pinching", leading to significant attrition. As a former Alphabet (not Google) employee, I can personally attest that Google money does not flow as freely to the ‘other bets’ as outsiders might imagine.

Tesla is far from being a traditional automaker, of course, given its wide array of products and connections; it did announce an android at the same product launch as the Cybercab. But conversely, Tesla will be particularly vulnerable on the question of competition for AI talent, given its choice to rely on cameras alone. By eschewing lidar in its vehicles, Tesla is dropping its production cost per vehicle significantly; but it is therefore relying that much more heavily on its development of AI self-driving capability to compensate. Yet the company must compete for the relevant talent not only with other automotive companies, but with also every major AI lab and tech giant.

The Road Ahead

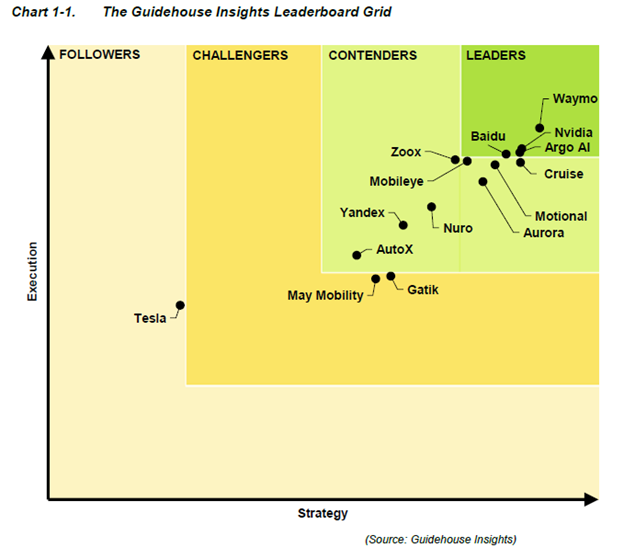

Every so often the consulting firm Guidehouse Insights publishes an update to its leaderboard of automated driving systems. Here is their take on the state of the field as of mid-2021:

In Guidehouse’s view, Tesla was being lapped by every other firm, and Cruise was in the Top Five, just behind Argo AI. Less than four years later, Cruise (and Argo AI) are no more; and wherever Tesla is, it’s surely no longer dead last.

The end of Cruise should remind us that building a world where automated driving is commonplace is hard. It was easy, once, to imagine that the technology would smoothly progress, and that would be enough. By contrast, today it’s easy to see all the difficulties facing the sector: technical problems, regulatory barriers, and competition for talent.

For Tesla, the road ahead looks particularly precarious. Just as with Cruise, there’s a misalignment between what the firm is good at, what it needs to do to keep making money, and what it would need to do (and how long it will take) to succeed in robotaxis. Conversely, Waymo, the most successful to date, doesn’t resemble Cruise at all: it has been patient, transparent, and courted regulators wherever it has gone.

I hope that the lessons all robotaxi firms learn from Cruise’s sad end is that robotaxi deployment is as a marathon, not a sprint; regulators are partners, not enemies; and success depends on a strong company culture that responds to adversity with humility and transparency. It all ended for Cruise because of one bad night; companies that fail to learn these lessons are gambling that such a night will never happen to them, not even once.

Off-Ramps will return next week (presuming that, unlike this week, there isn’t a sudden and important development in innovative mobility)

A couple of things about automated vehicles... The threshold for success is SO much higher than for conventional non-automated travel. We note that one incident in California shuts down a billion-dollar company, while on that very same day there were were no consequences from the likely dozens, if not over a hundred, fatalities due to non-automated "regular" travel. A Tesla burning up makes international headlines, while a "regular" car fire is noticed only by its owner and some passersby. We are in a situation where "perfection" is the enemy of "good".

Secondly, I still struggle to understand the role of bicycles, pedestrians, and motorcycles in an automated vehicle world. I haven't seen a "self-driving motorcycle" (indeed, what would be the point), it appears that cycling (including e-bikes, scooters, and the like) would ultimately need to be physically (and temporally) separated from automated vehicles, and I envision pedestrians simply crossing streets at will, safe in the knowledge that every vehicle on the road is programmed to avoid it. Certainly a good Friday night university party would involve a bunch of frat boys drunkenly strolling down a freeway or hanging out in the middle of a busy intersection while self-driving vehicles work their way around the obstacle.

On the other hand, I do look forward to the revolution in traffic operations, efficiency, and safety when all traffic signals are eliminated due to the ability of the vehicles to operate within a giant "cloud" of operational data that automatically pushes each vehicle through a limited space in the most efficient manner possible. Of course, our cyclists and pedestrians will have to have their own physical (bridge / tunnel) and/or temporal (ped crossing signal) separation devices to allow them to share the road corridor with motorized vehicles.

We'll see....