Robotaxis, Don Draper, How Our Culture Treats Boys, and 100 Billion Neighbours

Off-Ramps for 5 December 2024

Welcome to Off-Ramps! Today I’ll highlight four interesting pieces that I think you will enjoy reading. Please enjoy these on your morning commute, or save them for your weekend.

1. Robotaxis Are Drinking Ride-Hail’s Milkshake

It seems obvious, in theory, that as robotaxis become more common, competition with machines will depress the earnings of the human drivers on ride-hail platforms. Supply and demand, and all that.

But the matter is no longer theoretical. It’s begun to happen.

Getting a handle on the scope of the problem is difficult, because neither the robotaxi firms nor the ride-hail firms want to acknowledge it exists. The former are following their go-slow, make-no-waves strategy; the latter don’t want to dissuade potential drivers from joining their firms.

Nonetheless, if you ask the drivers themselves, they’ll tell you.

They’ll tell you in the United States (hat tip to Reilly Brennan):

Jason D., a 50-year-old Uber driver in Phoenix, told Business Insider it had become harder to make money in recent years because of increased competition with other drivers, lower fares, fewer tips from riders, and higher operating costs. Now, he said, the rollout of Waymo One robotaxis has made this problem even worse.

"Driverless taxis are flooding an already competitive Phoenix market and taking money from human drivers," said Jason, who drives full time and asked that his last name not be included for fear of professional repercussions.

They’ll tell you in China:

Liu Yi is among China's 7 million ride-hailing drivers. A 36-year-old Wuhan resident, he started driving part-time this year when construction work slowed in the face of a nationwide glut of unsold apartments. Now he predicts another crisis as he stands next to his car watching neighbours order driverless taxis. "Everyone will go hungry," he said of Wuhan drivers competing against robotaxis from Apollo Go, a subsidiary of technology giant Baidu…

China's Ministry of Industry and Information Technology declined comment.

The robotaxis are coming for ridehail. It’s up to us how we respond: we can either keep paying too much for people to do jobs that machines can do better, or we can embrace automation and invest in helping people transition to better industries. Let’s make the right choice.

2. Don Draper Lied to You

Are we surprised? We are not. Lying was Don’s whole thing, after all. But to what lie in particular do I refer?

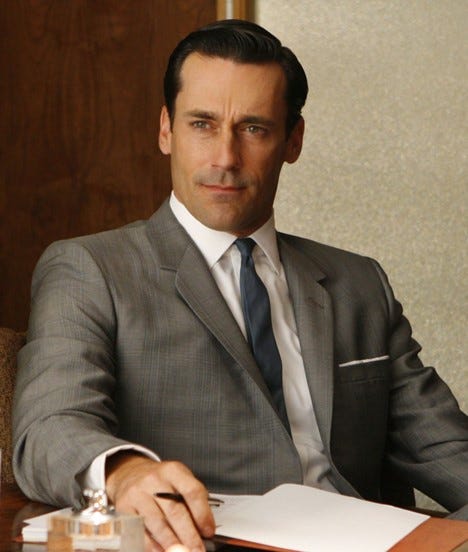

Jon Hamm as Don Draper on Mad Men (Episode 1.10: "Long Weekend"); probably deciding what lie to tell next

Why, that a good advertisement associates a product or service with a positive memory or feeling, such that when given the opportunity to purchase it, that positive feeling returns, encouraging you to buy it.

In case you don’t know him, Don Draper is a fictional character on Mad Men, a prestige TV show. Don is an advertising executive, and one of the subthemes of the show was the advertising campaigns he and his firm created. Towards the end of the first season, Don is tasked with selling Kodak slide projectors, and he says:

There is a rare occasion when the public can be engaged on a level beyond flash, when they have a fundamental bond with the product… It’s delicate but potent… it takes us to a place we ache to go again.

Don may believe this. The show’s writers may believe this. But it isn’t true.

Kevin Simler points out that account, which he describes as the “emotional inception” theory of advertising, is “decidedly Pavlovian”:

I'm shocked at how irrational it makes us out to be. It suggests that human preferences can be changed with nothing more than a few arbitrary images. Even Pavlov's dogs weren't so easily manipulated: they actually received food after the arbitrary stimulus…

But most ads are toothless and impotent, mere ink on paper or pixels on a screen. They can't feed you, hurt you, or keep you warm at night. So if a theory (like emotional inception) says that something as flat and passive as an ad can have such a strong effect on our behavior, we should hold that theory to a pretty high burden of proof.

…I know it's popular these days to underscore just how biased and irrational we are, as human creatures — and, to be fair, our minds are full of quirks. But in this case, the inception theory of advertising does the human mind a disservice. It portrays us as far less rational than we actually are. We may not conform to a model of perfect economic behavior, but neither are we puppets at the mercy of every Tom, Dick, and Harry with a billboard. We aren't that easily manipulated.

Ads, I will argue, don't work by emotional inception.

So if Don was lying, what is the truth? How do ads work?

For the answer, read the whole thing.

3. How Our Culture Treats Boys

Speaking of advertising, Joe Heath has concerns about how we market clothes for children. (Or he did, back in 2018, but I see no evidence that anything has changed.) He describes a visit to a children’s-clothing store, and seeing the following shirts, marketed to girls:

And the following shirts marketed to boys:

He notes tartly that

It should go without saying that, if the genders were reversed, and boys were currently being sent the messages that are currently being directed at girls, we would not hesitate to describe it as sexist. So I hope it is not too controversial to describe the current messaging as “reverse sexism.” Girls are being encouraged to be smart, to be successful, and to become powerful. Boys are being encouraged to be lazy, to work less hard, and to be stupid. In other words, it’s not just that girls are being encouraged to strive for success, but boys are being encouraged to develop habits that will lead them to failure in life.

I have noticed this current in our cultural life myself. Taking this together with Simler’s article in the previous item, the conclusions one draws are disquieting. I’ll spare you any observations on our contemporary politics. Instead, I’ll quote Dave Eggers:

We have advantages. We have a cushion to fall back on. This is abundance. A luxury of place and time. Something rare and wonderful. It's almost historically unprecedented. We must do extraordinary things. We have to. It would be absurd not to.

Even though it’s a bit long, that’s a message I would love to see on a T-shirt.

4. One Hundred Billion Neighbours

As a member of Generation X, I grew up in the shadow of Paul Erlich’s The Population Bomb. Yes, we worried about was nuclear war and human extinction; but that was only the most baroque fear. If we managed to survive that, we would instead suffer a different kind of destruction. Not climate change (or rather the “greenhouse effect” as we called it then), but overpopulation. As the human population outstripped the carrying capacity of the Earth, we would suffer all kinds of privation: food, clean water, green space, and homes. We would choke on our own pollution. Life would be miserable.

This was a running theme of films like Soylent Green or Logan’s Run, or the original run of Star Trek (see “The Mark of Gideon”). The theme persists today: Thanos, the genocidal villain of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, is motivated by a fear of life outstripping the resources needed to sustain it. I’m not the first to notice that the films don’t completely repudiate his views.

As such, it was delightful to read Tomas Pueyo’s spirited argument that Earth could not only support a population of 100 billion people, but also could do so comfortably, with everyone enjoying a high quality of life, and with the natural world flourishing, even more than today.

Where would they live? Some in megalopolises, some in built-up mid-size cities, and some in rural areas. We have the technology to make cities dense enough for this

What would they drink? Desalinized water

What would they eat? Efficiently produced crops, vegetables from vertical farms, meat from labs, fish from aquaculture

Where would the energy for all this come from? Mostly solar, some nuclear

And Tomas’ brio doesn’t stop there. He asserts that such a world would be better than the alternative:

A world with 2 billion people would be decaying, poor, brutal, violent, hopeless. A world with 100 billion people would be dynamic, rich, innovative, peaceful, hopeful. I’ll prove that to you today.

I really enjoyed these pieces. Not because I think we will achieve such a world; Tomas himself notes that the UN thinks the total human population will top out at 10 billion toward the end of the century… and that is probably too generous, with Peak Human coming sooner than that, and at a lower number.

I enjoyed them because, firstly, Tomas is dreaming big, and we don’t have enough ambition like that right now. But secondly because what is true of the Earth is true of North America: we don’t have enough people.

More people allows more innovation, more specialization, more economies of scale, more learning curves, and better network effects. There’s more production, more consumption, more of everything. There’s also more pollution, but as Tomas notes, we have the energy and the technology and the tools to solve this; and the more of us there are, the easier it is.

The United States is probably underpopulated relative to what would be ideal. Certainly Matt Yglesias thinks so: that’s why he wrote One Billion Americans. But that’s not for me to speculate about.

But the population of Canada absolutely is for me to speculate about, and I agree with Doug Saunders, who wrote Maximum Canada, that we should be aiming for 100 million Canadians. We’d need to build a lot more houses to put everybody, but again, we should be doing that anyway.

Such a country would have a big enough internal market to build things, to innovate, to cease being a branch plant or a supply centre to the world and start being a serious place. As Saunders puts it, it would be “a country that stays open all night”.

To go back to where we began this post: in this, in robotaxis, in so many things, we can choose to dream big, or we can choose quiet stasis and genteel decline.

Let’s choose to dream big.

This reads like a hit piece on the European Union. Genteel decline is what the former colonizers deserve! Of course you are not supposed to include the Turks, the Arabs, the Vietnamese,..., and all the others as colonizers, ONLY the white people. Only white people are so wonderfully self-reflective as to understand their ancestors mistakes. The funniest part is that the people who think this way genuinely believe that they are not racist. The entire post-modernist outlook is fashionable white supremacy.

Your writing is going against the program. You need to talk about guilt and provide statements about the First Nations!

In all reality your point is wise, but it is difficult for politicians to avoid terrible decisions. The US constitution's number one job was to stop politicians from making stupid decisions. The average person insists that "We must do something." That something is wrong 99% of the time, or perhaps more, but it feels good to do something. I am reminded of the moronic increased fuel economy standards placed on US carmakers ten years ago or so. The result was that they stopped producing cars and produced trucks and SUV's with worse fuel economy. The legislation had the exact opposite effect that the planned one, and the politicians who backed the bill refuse to alter it, because it was as a "green" piece of legislation.

The only force that can save us is gridlock. We need to find new and innovative ways to stop government officials from breaking anything else.