The City of Burlington is the most westerly of Toronto’s suburbs. Recently, elected officials there asked City staff to consider whether Burlington transit should stop charging fares.

The City is following a trend. In the past few years, many cities and towns in North America have experimented with fare-free transit. Elsewhere in Canada, smaller places like the relatively-tiny town of Orangeville have gone fare-free. Some larger Canadian cities are considering the idea, and the opposition party in Nova Scotia has indicated they would eliminate all fares in the province if elected. In the USA, the trend has been embraced by places like Richmond; Olympia; Tucson; and, on some routes, Boston. These efforts are largely cautious pilot measures, but they stand alongside the permanent abolition of transit fares implemented in European places like Tallinn, Dunkirk, and the entire island of Malta, or—in Asia—Jakarta and Kuala Lumpur.

Any jurisdiction willing to attempt innovation in the delivery of public transit deserves praise. But going fare-free is not innovative. It’s been tried many times, and been proved to be a bad idea. Going fare-free increases costs, worsens the quality of service, and competes with better ways to improve transit.

Before explaining the case against, let's explore the case for. Why does this idea have so many advocates?

The case for fare-free transit

Let's begin with the most obvious argument in favour, which is that going fare-free will benefit riders. Transit patrons get to keep making transit trips, but save the money they would have spent on them. This would not be trivial: Canadian and American households spend, on average, between 13 and 16 percent of their annual income on transportation, making this category of spending the second-highest, after housing. And that average conceals the fact that the lower the household income, the higher the percentage spent on transportation is. Lower income people have less flexibility finding work, and so have to spend what it takes to get to their workplace, no matter how expensive it is. Relieving these burdens would be a clear win for riders, and the poorer they are, the bigger the win.

So going fare-free helps riders. It would also help transit operators, by boosting ridership. It’s not a coincidence that so many US cities launched their fare-free pilots in the past few years: ridership on their transit systems collapsed during the Covid pandemic. The fear was this ridership drop might inspire a “doom loop”, the vicious circle where falling ridership would require operators to reduce service, which would cause ridership to fall further. To escape this vicious cycle, operators embraced a variety of drastic measures. Going fare-free was one such, made feasible courtesy of generous subsidies from the federal government.

There is ample empirical evidence that implementing fare-free transit increases ridership; in North America, different operators have been experimenting with fare-free service since the 1970s, and the results were clear. Denver, for example, went fare-free in 1978–79 and reported ridership increases of 36 to 49 percent; Austin tried it in 1989–90 and enjoyed increases of between 30 and 75 percent. In the present day, Richmond reports that after going fare-free in 2020, 28% of its riders in 2023 had not used its transit service before.

Increased ridership yields all sorts of good outcomes. More transit riders mean fewer car trips, as some of these riders would otherwise have driven. That means less road congestion or competition for parking. That’s good for drivers, but fewer car trips is also good for society as a whole, because of reduced pollution. Operating a car pollutes in a variety of ways, so less car use means less pollution.

You might think that benefit will become less salient over time. As cars go electric and power grids go green, won’t cars emit fewer greenhouse gases? Yes, that’s true, the engines will be less polluting. The tires, however, will continue to emit toxic particulates, and absent innovation in tire design, they will continue to do so.

ChatGPT's interpretation of a fare-free world

Other benefits are more abstract. As more people use public transit, its political constituency grows, giving it more political clout. Transit is a public good, and as such it’s in an eternal struggle against other public goods for government funding. From an operator’s perspective, more riders makes it easier for transit to outcompete its rivals. Those include not only direct competition like highway construction, but also indirect competition, like education. The more users a transit system has, the harder it will be for politicians to cut its funding, even if those politicians never use transit themselves.

Most speculatively: more public transit use creates more opportunity, or even pressure, for cities to realign their use of public space away from auto-centricity to human-centred use. If everyone takes the bus or the subway, the argument goes, it will be easier for cities to relax parking minimums and other regulations that promote cars over other modes of urban travel. This is good because the presence of cars and car-related infrastructure is antithetical to everything that makes cities great. On this, liberals and conservatives can agree: in urban contexts, cars pollute, make noise, waste space, block pedestrians, endanger cyclists, and inhibit everyone.

If going fare-free is so great, why does any agency bother to charge fares at all?

There are benefits to going fare-free beyond increased ridership. One might be better efficiency: if there are no fares, that means the system doesn't have to invest time and money collecting them. So subways can tear down their gates, removing the friction of waiting to get in or out of the station. Buses don't need to wait to collect passenger fares, reducing their dwell times at stops, speeding up trips.

In some cases, security improves as well. In Canada and the USA, cash has largely been phased out in favour of farecards, open digital payments, or other fare media. But this isn't universally so, especially in Central America, South America, and Africa. Many operators still accept cash for fares and even have a political mandate to do so. In cases like this, the presence of cash on transit vehicles (typically buses) means that:

drivers become targets for robbers, and

drivers have the opportunity and temptation to be robbers themselves, pocketing fares rather than remitting them to the agency, or

the agency must invest in fare security to prevent both outcomes, which costs money while worsening customer service.

Going fare-free obviates all three problems.

The case against

These arguments seem strong. Indeed, they seem to be too strong. If going fare-free is so great, why does any agency bother to charge fares at all?

More to the point, why have any agencies that experimented with not charging fares ended that experiment? I noted earlier that Austin and Denver did just this in the 1970s; so too did Salt Lake City, and later, Topeka, and Milton (in Ontario, about 20 km away from Burlington). More recently, Kansas City is considering ending its Covid-era fare-free pilot, and New York City ended its experiment with a few fare-free bus lanes a few weeks ago.

Presumably, these jurisdictions abandoned their fare-free systems because, for them, the disadvantages of going fare-free outweigh the benefits. And what are the disadvantages? The first and biggest one is that it increases ridership.

That may seem perverse. Didn't we already cite increased ridership as a good thing? It’s complicated. Increased ridership can also lead to all sorts of problems.

Being forced to pay for a thing signals that it is valuable.

Firstly, more riders mean higher maintenance costs. The amount of wear-and-tear a transit vehicle incurs relates to the number of riders. More riders mean:

more dirt,

more litter,

more vandalism,

higher fuel costs, and

faster deterioration of vehicle components, such as brakes, suspension systems, or tires.

These costs have always increased with ridership, in indirect fashion; each new rider at the margin typically brings more fare revenue than they impose in costs, so ridership growth is in an operator's interest. But going fare-free removes all fare revenue even as it supercharges ridership, meaning that net operating costs skyrocket.

Transit agencies are usually starved for revenue. It's worth remembering that almost no transit agency in the world can cover their operating costs with fares. The few exceptions—Hong Kong in most years, and Singapore, Taipei, and Tokyo in some—operate with extreme efficiency in places with high population density. Even these systems rely on government subsidies for capital expenses.

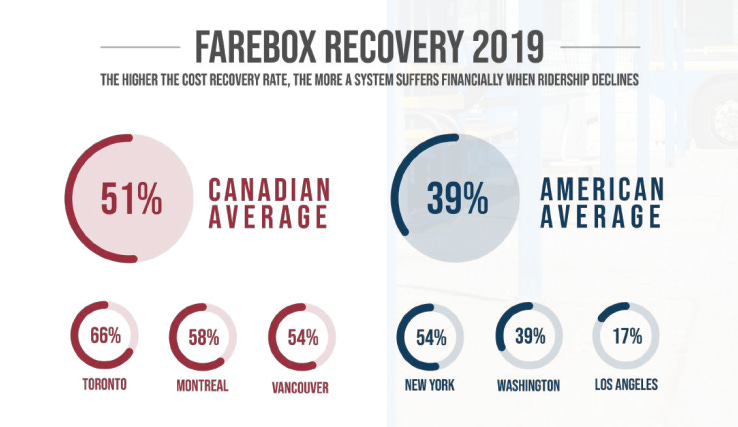

So fare revenue covers only a portion of what a transit agency needs to operate. The extent to which this is true can be quantified, using the metric of the ‘farebox recovery ratio’, which divides annual fare revenue by operating costs:

Source: Canadian Urban Transportation Association, Why Public Transit Needs Extended Operating Support, 2021

As per this chart, in 2019 Toronto’s TTC required a subsidy of a dollar for every two it got in fares, and New York's MTA, the North American system with the highest ridership, needed almost a one-to-one subsidy, with other systems performing much worse. This suggests that the MTA would require at least a doubling of its public subsidy to continue operating fare-free. Doubling would permit them to cover the costs of their existing ridership, but they would need even more than that to offset the incremental costs of their new ridership. It is difficult to imagine any government being willing to provide such an increase in operating subsidy, given how many other pressing demands there are for funding.

Money isn't the only problem. Increased ridership means more crowding, too, as additional riders pile onto the same vehicles. So going fare-free can also lead to the system becoming less accessible, and the use of the system becoming less pleasant. With so many new riders having to board or alight from the vehicles, the time gains from not having to collect fares may be offset, meaning any expected gains to trip speed don’t materialize.

Nor are the new riders representative of the previous set. While some new patrons will be those who could have afforded to take transit, but previously chose not to, most will be those who could not have afforded it before. So the marginal new rider will be someone for whom having to pay a fare was a material cost. While this makes transit more accessible, it may also lead to an increase in other problems.

Being forced to pay for a thing signals that it is valuable. Making it free signals that it is not. And it's human nature to treat things that have no value carelessly or with contempt.

So the increase in ridership tends to also lead to increases in things like violence, vandalism, and other forms of unpleasant behaviour. These are their own vicious cycle: disorder on the system drives away users who have other options, meaning that the system becomes more disorderly. Consider that agencies in locations as diverse as Texas, New England, and Ontario who tried fare-free operations reported that increased rowdiness, to the point where it posed danger to transit staff, was the result.

All of these problems admit of solutions, of course. An operator might, given time, reduce crowding by running more vehicles; it might reduce abuse of the service, or of passengers, by having more security presence. But these solutions all cost money. And the consequence of going fare-free is having less money to make investments like these, not more.

The better way

Public-transit agencies understand these things. Typically it is politicians who do not. Notably, in Burlington, it was elected officials who have floated the idea of going fare-free, not the operator.

The most productive way to think about going fare-free is as a project. It might be construed as a project to increase ridership. By reducing fares by X, or eliminating them entirely, we'd gain ridership of Y; and it would cost roughly Z. Put in these terms, an operator can compare this project with other ones, which will also increase ridership or produce other benefits, for a certain cost.

Alternatively, it might be construed as a project to help the poorest residents of a city, to help make their lives more affordable. By reducing fares by X, we’d put Y money back in riders’ pockets. A government can compare this project with other ones, which also put money in the hands of riders, for a certain cost.

There are better projects for both transit agencies and governments to consider. Agencies could run service to new areas by extending bus or subway or train lines. Or run existing service, but more frequently, so riders have more options. Or fix problems that make trip times slower or less predictable than they should be: resolving 'slow orders' on rail lines, or getting segments of roadway made bus-only, or something else. As Matt Yglesias has noted, in most cases these projects pencil out better financially, while also resolving the problems experienced by existing patrons. For their part, governments could provide targeted subsidies to poor residents: food stamps, job training, or just give cash.

As suggested in the subtitle, there are some edge situations where going fare-free deserves serious consideration. A small but growing town that is poised to introduce transit for the first time may want to begin with the service being free, to boost ridership, and to defend a nascent operation against the grumps who write angry letters every time they see a bus with few passengers on it. Though it's not a slam-dunk case. It can be dangerous to teach your customers that your product should be free, and then try to persuade them to pay for it. See also: newspapers and the Internet.

And tourist towns like Mont-Tremblant, with its ski resort, or Canmore—not itself a tourist destination but adjacent to one, namely Banff—have good reason to make their systems free. Fare-free service simultaneously keeps drunken visitors off of unfamiliar roads, while acting as a subsidy to service workers, who earn wages in expensive resort areas but can't afford to live there.

But none of these circumstances apply to Burlington, or indeed most places. Which is why I'm pleased that the fare-free trend seems to be ending; public transit is valuable, and we shouldn't be ashamed to pay for it.

Respect to Andrea Taylor for feedback on earlier drafts.

Thanks for reading Changing Lanes! Please let us know how we’re doing by taking the poll below. And if you’d like to respond to this post, please leave a comment.

Good coverage of all the arguments!

I don't know if free public transit is necessarily the right way, but my concern of it having fees is that it is in stark contrast with the other cost of transport - roads.

Most roads are 'free' - and this 'free' part results in the same as issues as above. Wear and tear is higher, congestion increases impacting others, slowing down of the system, 'vandalism' in the form of littering, speeding and car crashes.

Moreover, roads are also not charged per user - so a family typically has much higher costs to use transit than a car. This creates highly skewed incentives that reduce economic output.

If every road had a toll, then there would be less of an incentive contrast.

Nice piece here Andrew. Generally speaking, there is little benefit to trying to run or hide from the “price signals” that determine the value of a good or service.

Someone always pays for it, somewhere. The question is who.