Progress and Public Transit: the Endless Emergency

What would progress in public transit look like?

In the past year I've attended conferences on mobility in both Canada and the USA. I always leave them with mixed feelings. It's a pleasure to spend time with intelligent people of good will who want to make our cities better, and make them easier and cheaper to traverse. But it's a pain to listen, again and again, to the same content, which is roughly as follows:

Transit service is falling short in some way

The solution to the problem is for government to provide more funding

Just in the past year I've heard this story from activists and advocates, who are mad about it. I've heard it from academics who have quantified it. And I've certainly heard it from Canadian and American mayors, and federal politicians, and state/provincial officials, who insist it's someone else's fault.

So transit service is poor, and remains that way. Improvements depend entirely on someone else writing a big cheque, which sometimes happens, but not enough to depend on it. So the system is always in a crouch: half the time whining that its poor service is not its fault, half the time begging someone else to bail it out. Meanwhile, riders tolerate sub-optimal service that never improves.

This is the endless emergency.

The endless emergency appears everywhere one cares to look. To make it concrete, let's consider only one transit operator, and the one I use: Mississauga Transit, which operates under the name 'MiWay'.1 Mississauga is Canada's sixth-largest city, serving around 59 million trips a year. That's small relative to Toronto or New York, but it's large relative to most North American providers; larger, for example, than Seattle, Portland, Denver, or Minneapolis–Saint Paul.

In the past year, MiWay has raised fares twice while offering less service than it did in 2017. It operated without a contract with its workers for almost a year and only averted a strike through last-minute concessions. It aspires to upgrade its stations, but that work is dependent on external funding, namely support from the national government through a public fund. An application is in the works.

I could multiply examples without limit, but the story is the same. Stories about transit, at any time, in any city, are usually negative because transit service, at most times and places, is falling short. There's not enough service, or not enough reliability, or not enough safety, or it's too expensive.

Because it's such a common story, it's easy to forget how abnormal this is. Most businesses are not like this. A restaurant chain that persistently offered bad food, or brought it late, or charged too much would go out of business. What makes transit different?

The difference, of course, is that it is public transit. It's owned by the public; open to all; accountable to government; and funded by government. It can't go out of business.

This is a good thing! Transit is absolutely necessary for cities to function. The urban economy requires large numbers of people to move from place to place: from homes to workplaces to commercial and recreational sites. Typically the distances involved make them too far to walk, and if everyone drove the roads would be congested to uselessness. The geometry and physics are unforgiving. Given limited space and limited time, the only way to move large groups of people is with large, shared vehicles. And to aggregate enough trips for the system to work, it has to be a system, a monopoly provider.2

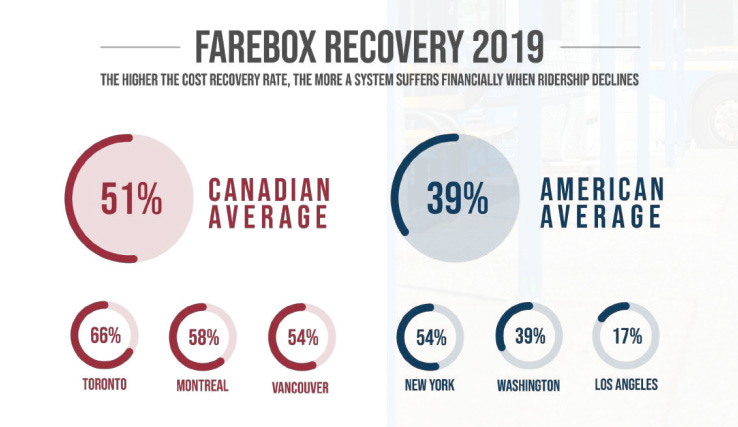

But it's also a bad thing. Transit is expensive to operate. It's so expensive, in fact, that everyone takes for granted that fare revenue covers only a portion of what a transit agency needs to provide service. Dividing an operator's annual fare revenue by annual operating costs gives the farebox recovery ratio:

Source: Canadian Urban Transportation Association, Why Public Transit Needs Extended Operating Support, 2021

To quote myself, when I argued that transit should not be free: "As per this chart, in 2019 Toronto’s TTC required a subsidy of a dollar for every two it got in fares, and New York's MTA, the North American system with the highest ridership, needed almost a one-to-one subsidy, with other systems performing much worse."

This chart explains why every transit conference's theme is how to get money from someone else to run the system. It’s because without money from someone else, the system couldn't work. Look across the entire world, and the number of transit operators that don't require operating subsidy from a government can be counted on one hand: Hong Kong in most years, Singapore, Taipei, and Tokyo in some.

Once again, because it's such a common story, it's easy to forget how abnormal this should seem to us. Without public transit, no major city could function. Transit connects residents to jobs, and businesses to workers and customers. It seems like it should be simple to raise fares to a level that will sustain the system... and yet no system in the world does it. Why?

The answer, in a word, is density. Transit thrives on density, and we don't have enough of it.

Density is crucial for transit to succeed. Transit's fixed costs are high and its variable costs are low: for any given trip, most of the cost must be paid to serve the first rider. Each rider after that incurs a slight variable cost, which is more than offset by fare revenue. In practice, that means a bus or a train trip makes money for the operator when it has lots of riders, but loses money when it has few. And the driver of ridership is density.

Successful transit connects a sufficient number of origins (where people live) to destinations (where people work, shop, or engage in leisure activities). Dense urban environments provide this critical mass of both origins and destinations within a compact area. This concentration allows transit routes to be more direct and frequent, serving more people more efficiently, and making more money for the operator. It's no coincidence that the few transit agencies that are able to turn an operating profit with any consistency are in Asian cities that are particularly densely populated.

North American cities tend not to be like this, because of the automobile.

As the automobile became ubiquitous in the early twentieth century, the fabric of urban life changed. Post-automobile suburbs sprawled, spreading fewer homes and fewer buildings over larger areas, with ample space given over for wide roads and parking lots. This urban form is well suited for car travel, but bad for transit. The low density of this urban form left bus operations on the horns of a dilemma.

They might offer bus routes as direct lines on major corridors, which would offer fast service, but only to the few riders near the corridor, leaving many without access to transit. Alternatively, they might offer routes on indirect lines: longer, meandering paths that would capture more riders, but force those riders to wait for long times at stops and then on their trips, making for unappealing and unhelpful service. Either choice encourages many potential riders to switch to auto travel, removing them from the pool of potential regular transit users permanently. One hundred years of this has left most of our urban areas designed for the car, leaving transit a mode for those who can't afford a car, or those who can't reach their destination because of congested roads.

…public transit is a ‘cost centre’ of the modern city, just as customer service is a cost centre of modern business

There are two ways out of this trap. Transit operators could charge more in fares, or they could cut service, eliminating routes that cost more to operate than they generate in fares.

Operators are not able to take either option in any serious way.

Charging more in fares might work, if a system could do it enough. Mild fare increases are common in every city, but large ones would make the service unaffordable to many riders, who would stop using the service. That in turn would mean the service would be in a deficit position, and need to raise fares to make up the difference, creating a vicious circle, or ‘doom loop’. Cutting unprofitable lines also might work, by getting rid of weak routes. Houston did this a few years ago, and MiWay did also, to good effect. But this is difficult to do more than once.

Whether they pick one or do both, no operator can do more than nibble around the edges of the problem, because each option defies the mandate to provide universal service. That mandate is baked into the concept of public transit: it is there to serve the whole public, which means everyone must have access. Less high-mindedly, the fact that riders are voters means that politicians insist to operators that service be universal. Operators cannot afford to defy them, given their need for subsidy.

This creates a particularly vicious cycle. Stipulate that additional operating funding arrives. This does happen, from time to time, because conditions deteriorate enough, or an elected official sees advantage in it, or riders engage in enough advocacy. This new funding gets captured in predictable ways, by both unions and management.

Union capture is straightforward enough. Transit operators are a closed-shop monopoly, and the service they provide is highly sensitive to even slight disruption. Given that environment, it’s no surprise that over time, wages and benefits devour any increase to operating spending, reducing service quality to the prior baseline. Indeed, for years after its foundation, the managers of Toronto’s commuter-rail system argued against receiving operating subsidy, on expectation that it would simply be captured, baking in unreasonable expectations of the part of labour that the system would eventually be unable to meet.

Management capture of operating funding is less obvious. Like any organization, a a transit operator must keep its capital assets in good condition; in transport jargon, this is called maintaining state-of-good-repair (SOGR).3 SOGR is necessary, but because of the nature of the business, it’s very hard from the outside to tell if an asset is actually in such a state. This means that funding for SOGR is a blessing to lazy or greedy management. SOGR is:

Necessary,

Morally and politically unopposable (“we have a duty to the citizenry to maintain these public assets, and ensure the system is safe to operate”), and

Very difficult to assess if it has been achieved.

These facts give management a lever to pry more funds from the government, which it can use for empire-building, nest-feathering, or simply coasting and not trying very hard. Alon Levy, the most knowledgeable voice on cost inflation in transit operations, is hawkish on this point; his solution to the “SOGR scam” is to regard “any request for funding for maintenance or replacement [as] a tacit admission the agency cannot govern itself and requires an outside takeover”.

This state of affairs is why requests for additional subsidy are constant, and yet never seem to solve the problem. Any new provision of operating funding, over time, gets divided up between workers and management, meaning that service quality may improve slightly, but eventually dips back to the previous baseline, but with a permanently-higher cost base. Farebox recovery ratios stay below 1. Every trip requires subsidization, or put another way, every trip costs the operator money. The more service it offers, the more money it loses.

And so: the endless emergency.

Anonymized Twitter users exemplifying the Endless Emergency. Note that the claim about BART is untrue; before the pandemic, BART’s farebox recovery ratio was between .6 and .7

Is there a solution? It may seem that there are only two possibilities. One is to accept that public transit will always cost more than a city can really afford, and to give up, dissolve the service, and let the market figure it out. Failing that, the other possibility is to accept the status quo as the best that is possible, and continue to limp along with service that perpetually falls short. Neither seems attractive.

We cannot choose the first. Indeed, to the best of my knowledge, no city that has offered public transit has ever abandoned it. And for good reason: affordable, accessible urban transportation is often a legal requirement, established by national and sub-national governments as a right to which residents are entitled. A ‘right’ is a strong claim, but reasonable on its face. Given the extent to which our cities and suburbs are now designed for the automobile, it’s impossible to get around without one, and yet many do not have a car, or cannot operate one. These include teenagers, the elderly, the disabled, and the poor, to name only four categories of resident. Providing public transit as an alternative to the car is a way to ensure all residents have opportunities to get around.

Beyond this, no city would want to eliminate public transportation. Urban economies depend on it, to help their workers reach their jobs and customers reach businesses. In this sense, public transit is a ‘cost centre’ of the modern city, just as customer service is a cost centre of modern business: it absorbs money, but because the long-term health of the whole organization depends on it, it cannot be eliminated. In fact, customer service is a good analogy. It is a necessary service, but one for which demand always exceeds the ability of the larger organization to support. Consequently it always falls short, leading to permanent dissatisfaction among users.

Does that mean we must choose the second option, and accept that the emergency will indeed be endless? I don’t think so. We have faced problems before that seemed so widespread and so intractable that they were less ‘issues’ and more ‘part of the human condition’, matters to be stoically accepted as just the way things are. And these problems seemed this way until the moment when a new technology solved them. Mortality in childbirth was an endless emergency, until penicillin was discovered. Fossil fuel dependency was an endless emergency, until solar panels could be produced at scale. And poor public transit service will be an endless emergency... until we try something genuinely new to solve it.

And genuinely new approaches are at hand. We will discuss them in a future issue.

Author’s Note

Firstly, today’s post is the first in a series. Changing Lanes is a newsletter with a few themes. One is progress, namely how the intelligent application of policy, technology, and investment can make the future better than the past. Another is mobility, namely how people and goods move from place to place.

For many kinds of mobility, we can see what progress is going to be. For long-range air travel, it is the return of supersonic flight. For short-range air travel, it's electric vertical-takeoff-and-landing flight (eVTOL), known colloquially as 'air taxi'. For personal vehicles and for ridehail, it's driving automation. All of these are interesting and will be the subject of future newsletters. But this series is about transit.

Transit is one of the principal modes of urban mobility today: shared vehicles, serving large numbers of passengers, on fixed routes. Unlike other modes, it's hard to see what would constitute progress here.

Today’s entry in the series has defined the problem. Future entries—parts two, three, and four— will propose solutions.

Respect to Jenni Morales, Julius Simonelli, Steve Newman, and Dynomight! for feedback on earlier drafts.

Off-Ramps Coming Up

I have decided to move Off-Ramps into a separate post, arriving Thursday mornings. Off-Ramps will be only three-to-five links, with brief commentary from me, and won’t restrict itself to pieces published on Substack. You will, I hope, enjoy reading it on your morning commute, or saving it for the weekend.

Changing Lanes on the Road (virtually)

I’m pleased to announce that next week, I’m offering a webinar on The Ever-Expanding Uses of Autonomous Vehicles. This will be the inaugural webinar in a series hosted by the Canadian Automated Vehicle Initiative (CAVI), an association for all stakeholders in the Connected and Automated Vehicle ecosystem in Canada. The webinar will describe how automated driving will appear, across sectors, in the coming years, paying special attention to the implications for our businesses, infrastructure, and economy; and the policy changes it will require. Though the examples will be primarily Canadian, the webinar will be of interest to people outside Canada as well.

The webinar is free of charge, and is happening on Wednesday, 20 November 2024, from 1100h to 1145h EST. You may register to attend here.

The service ditched the stodgy brand "Mississauga Transit" in 2010 in favour of "MiWay", a name which supposedly sounded younger and hipper... because of its association with the Sinatra song. You know, the one that was released 41 years earlier.

This is frequently done for both political and physical reasons. Political, so that there is only one actor to fund or direct; physical, because many routes simply can’t permit competition—no city can have two competing subway tunnels that serve the same stations, for example.

It’s always annoyed me that this is called ‘state of good repair’ rather than the more grammatically-correct ‘good state of repair’, but SOGR is the universally-accepted term of art.

Having been to the developing world a few times, it's interesting to see how the problem is managed* there. in some areas, "public transit" is essentially a private business... vehicles run on set routes, but the schedule is "the trip starts when there are enough people on board to make it worthwhile for the driver to start the trip". I remember once taking a bus from Allenby Bridge (border between Jordan and the occupied West Bank) to Jerusalem. Six or seven of us sat and sat on a shuttle bus until finally a passenger in exasperation pulled out the equivalent of three or four more fares and gave them to the driver... now the bus was "full" and we could get going.

*I originally used the word "solved" but that's not much of a solution is it?

What would "progress" in public transit look like is such a great question! Eagerly anticipating the rest of the series.