Driving Automation Will Reshape Time and Space

And an important announcement about the future of Changing Lanes

Today’s post is drawn from my forthcoming book, co-written with John Niles and Bern Grush. Specifically, it relies upon arguments made in part of Chapter 3, “The Broad Context of Change”. If you enjoy this post, I encourage you to pre-order the book.

Before we get into the post, though, I have an important announcement to make about the future of Changing Lanes.

This newsletter began half a year ago, in September 2024. Since that time, I've published a new piece each Tuesday at an average length of 2,500 words. In our inaugural issue, we explored why Tesla Isn't Going to Succeed in Robotaxis. Since then, we’ve looked closely at what driving automation will mean: why The Cruise Shutdown Is Bad News for Tesla, and the thorny problem of Automated Driving in Winter Conditions.

Public transit has also been a matter we’ve looked at closely. Last fall, we thoroughly reviewed what ‘progress’ might mean when applied to public transit, in a four-part series on The Endless Emergency. Along the way, we’ve considered Why We Should Have Known Hyperloop would Fail; how Orwell Was Right About Progress; and why Canada Shouldn’t Build High-Speed Rail.

And since November 2024, I've supplemented these Tuesday deep dives with 'Off-Ramps', a special Thursday edition highlighting key work by other writers.

It's been a pleasure building a community that is interested in, and excited for, a future of mobility, abundance, and progress.

It's now time to take the next step.

I'm excited to announce that, beginning 6 May 2025, most Tuesday editions of Changing Lanes will become exclusively available to paying subscribers.

You may pledge to become paying subscriber now by clicking this link.

Here are answers to questions that you may be asking:

Why is this happening?

This shift will allow me to invest more time in research, data analysis, and reporting, to make Changing Lanes more valuable. It will enable deeper coverage of technical developments, regulatory shifts, and market dynamics in the innovative-mobility space. And, importantly, it will help me to pay my bills. I enjoy writing this newsletter, but after seven months of doing it as a labour of love, it's no longer sustainable as one. If I am going to continue writing, it must be a professional activity also.

When I subscribe, what will I get?

All Tuesday issues, with their deep-dive analyses

Access to the complete archive, from its September 2024 inception onward

Opportunities to suggest topics for future posts

Ability to comment on posts; commenting will no longer be available to non-subscribers

How much will a subscription cost?

$10 on a monthly basis, $99 on an annual basis.

If I'm not ready to subscribe yet, what will I still have access to?

All Thursday issues of Off-Ramps

Occasional Tuesday issues that I publish openly

Some pieces in the archive

May I become a charter member?

Yes, you may! If you subscribe before 6 May, you may join as a Charter Member, and pay the rate of $8 on a monthly basis, or $80 per year. That's 20% off the regular price. I’m offering this discount to you, my first readers, as a token of my appreciation that you’ve elected to support me now, at the earliest phase of the newsletter, when I need it the most. If you click through this link, you may subscribe now!

For your information, you won’t see a ‘Charter Member’ tier, just the $8/$80 regular tier. On 6 May, those rates will increase, and the opportunity for charter membership will end. You will see a founding membership tier, where you may subscribe for higher rates; there is no additional benefit to readers at that level, other than my gratitude for your generosity.

I'm making this change to ensure Changing Lanes continues delivering the best insight into mobility, innovation, and progress that I can offer. I deeply appreciate your readership, and look forward to continuing to write for you in this next phase.

The average American drives for about an hour a day.1

Given this data point, a Fermi estimate says that globally, at least 2 billion hours are spent each day on the driving task. If we stipulate 8 billion people each with 24 hours in a day, that means that, on any given day, approximately 1% of all human time in the world is spent driving.

This matters because driving demands our attention, which is the most finite of human resources. While a driver might listen to music or converse with passengers, the driving task still consumes significant mental bandwidth. It’s difficult to watch the road while adjusting the music playing in the speakers, and it’s impossible to watch the road while also looking in the rearview and side mirrors all at once.

This limitation on attention is fundamental to human cognition. It means that, unlike other resources—money, food, energy—attention cannot be manufactured or expanded. It is irrevocably capped by human biology.

This limit might not matter if we could make our days longer, or do two things at once, but both are impossible. Longer days are obviously impossible; there are 24 hours in a day, and more cannot be added. The fact that multi-tasking is a myth is not obvious, but remains true: the human brain cannot focus on multiple things at once. When you try to multi-task, you don’t actually do two things at once, you switch your focus rapidly between those things, performing each task worse than if you had focused on it exclusively.

This biological limitation makes attention extraordinarily valuable. Tim Wu called the industries that capture, direct, and monetize our focus “the attention merchants”. They include, but aren’t limited to, all forms of entertainment and all forms of marketing; they depend on capturing and harnessing attention.

Let’s do two final Fermi calculations. The market in advertising, last year, for the whole world was about $600 billion, all of it spent in pursuit of human attention. On most social media platforms, like Facebook, Instagram, or X, non-targeted display advertising costs ten cents per minute of engaged attention; the same rates apply to banner advertising in free-to-play mobile games and such. By that measure, the attention currently locked up in American driving alone is worth more than $400 billion annually; or two-thirds the total value of the attention paid for today. And that's a conservative estimate; for premium content or wealthier demographics, attention commands much higher prices.

Driving automation is about to release this vast reservoir of human attention. Which prompts the question: if we free our minds from driving, what will we do instead? The attention merchants are already positioning themselves to answer that question for us.

The release of attention will transform our world in at least three ways: it will change how we spend our time, as newly liberated attention is captured and monetized. It will change how we choose to live, as our relationship with distance and commuting will be fundamentally altered when travel time becomes productive or enjoyable. Finally, it will save lives by eliminating human attention failures that lead to crashes and fatalities.

Let's begin with the economic gold rush, which is already underway.

The Economic Gold Rush

The competition for newly-liberated attention on the road will be fierce. Who will want it?

In most cases, your employer will be first. Remote work has already blurred the line between work time and personal time, and increasingly the commute will fall into the former category.2 For knowledge workers, the vehicle will become another workspace for virtual meetings, e-mail review, and document preparation. Employers and employees will have to determine new boundaries around when work is to happen.

This change will be the least disruptive to the status quo, because so many transit commuters are already using their time this way, so there is precedent. Most transit vehicles in the morning rush feature people using their phones to handle e-mails. But only commuter-rail trains have anyone using a laptop to work on a presentation; subway cars and buses are less well equipped for office work. And the need for discretion prevents many from taking calls, as do norms around noisy disruption (though, post-pandemic, these are eroding). Private vehicles, though, can be optimized for all of these activities, and one can expect employers to demand their workers seize that opportunity to do more work.

Next up will be streaming video companies, who will welcome the prospect of extending their service offering to captive audiences. Netflix and YouTube have already partnered with Kia and Hyundai to offer streaming video when vehicles are parked, while Max and Peacock are available in Google’s Android Automotive infotainment platform. Full automation will extend this to moving vehicles.

Other forms of entertainment will follow. Video games, certainly; Tesla vehicles already feature games to be played on the display screen while the car is parked. Once driver attention is no longer required, that restriction will certainly be removed.

Analog activities round out the list: books, for one. Eating, for another. Drivers already eat one-hand meals like hamburgers; two-hand meals will join them. And other carnal activities too: according to the San Francisco Standard, it is already the case that “San Franciscans are having sex in robotaxis, and nobody is talking about it.” (Au contraire; I think lots of people are talking about it.) This kind of entertainment will not be the sort that makes anyone any money, though.3

Different business models will approach this opportunity in their own ways. Driving automation will express itself in two distinct markets: one for owning rides, i.e., privately-owned vehicles, and another for buying rides, i.e., automated ridehail. Exploring why this is true, and the implications of the split, is the central concern of The End of Driving.

In the former case, privately-owned automated vehicles will become extensions of the owner’s digital life, integrated with their other devices and services. In this model, one’s car becomes, even more than it is now, an extension of one’s living room or office; a place to sit and engage with screens. Automobile manufacturers will want the car to be the intermediary between occupants and other activities, and to extract value from every transaction. Cars today feature too many large screens; as the screen ceases to be a safety-critical control interface, carmakers will strive to make it the entertainment interface, through which other applications must pass, and be charged for the privilege. Some attention merchants will indeed pay; others will seek to make the occupant’s smartphone the interface, and the car screen merely a passive recipient of material broadcast from the phone.

The battles between the attention merchants and the carmakers will be epic.

I won’t predict who will win these. I’ll restrict myself to the observation that the attention merchants will have a strong edge, as most people are familiar and comfortable with their personal devices, due to long familiarity in a variety of contexts. Conversely, we might expect riders to be less willing to interact with unfamiliar in-car screens and interfaces. If I am right about this, the obvious play for robotaxi fleets is to monetize attention through advertising and sponsored content, using the lever to hand: pricing. The cost of a ride might be subsidized in exchange for watching advertisements, much as ad-supported streaming is cheaper than ad-free options. The truly dystopian vision here is one where in-car cameras monitor the gaze and don’t give the discount unless the passenger is judged to have actually watched the ad closely.

The efforts to monetize our attention will reshape how we spend our time in vehicles. One consequence of that reshaping will be changes to the kinds of trips we take.

Time, Space, and Perception

When driving no longer demands our attention, our relationship with distance itself will change. The way we experience travel time—and the choices we make about where to live and work—could transform in ways that reshape our cities and communities.

Currently, commuting is largely dead time, a cost that must be paid to traverse the space between the places where we actually want to be. And it’s not a fixed cost; a 30-minute drive through heavy traffic in the rain feels much longer than a 30-minute drive in good weather, much less 30 minutes doing entertaining things.

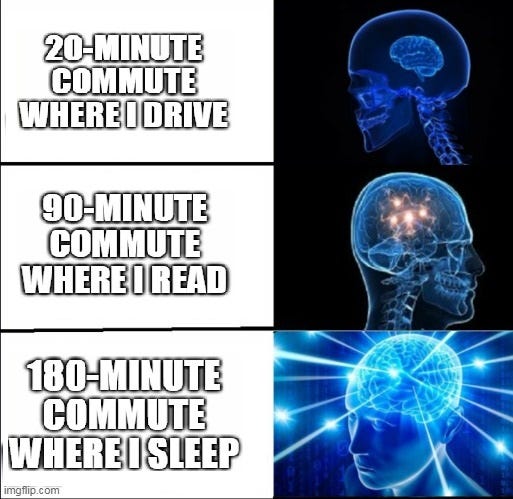

Automation changes this equation. If one can read, work, watch screens, or nap during a commute, the psychological cost of that commute will plummet. A 45-minute trip where you can be productive or entertained may feel less burdensome than a 20-minute trip where you cannot do these things. This relief is already a feature of public transit, which advertises it as a benefit it can offer that driving one’s own car cannot. Of course, on transit vehicles, one typically shares the space with strangers… and one may do just this in robotaxis as well. Such sharing imposes its own burdens and boundaries. But in a privately-owned automated vehicle? The psychological cost of commuting will dwindle.

The foreseeable consequence is that as driving becomes less burdensome, people will accept longer commutes. We've seen this pattern before. Humans have maintained roughly the same time budget for commuting—about an hour per day total—across different eras and technologies. But the distance covered in that hour has expanded dramatically with faster transportation methods. When omnibuses replaced walking, and trains replaced omnibuses, people didn't save time—they did not reduce the time spent travelling; instead, they lived farther from work.

Automated vehicles could accelerate this pattern, or even break it. The hour’s limit on travel, known as ‘Marchetti’s Constant’, has depended on the fact that travel was costly: of time, of energy, and—in the case of transit use—tolerating the company of others. If commute time can be used productively or enjoyably, and crucially alone, many people may find it economically rational to travel longer. In this case, they will live farther away from their workplaces, to take advantage of lower housing costs, more space, or more amenities.

That is to say, if we let them, the suburbs will sprawl even more.

If this prediction is accurate, its implications for urban planning and land use are profound. Dense urban centers might lose some of their premium if proximity loses some of its value. Conversely, previously sparse areas within a one or two-hour radius of employment centers could boom.

Out of these individual choices looms a collective problem: more and more road congestion. The Jevons Paradox will continue to bite: the technology that makes longer commutes more tolerable also enables more commuting, leading to even longer commutes. (Yes, driving automation could make road use more efficient through closer following, merging at speed, and so forth; but the logic of induced demand means that such improvements will only increase appetite for driving on the margin.) So driving automation has the potential to hollow out downtowns; encourage sprawl; and increase congestion, even as it will allow some individuals more pleasant and refreshing trips.

Depending on your values, this is a vision either of heaven, or of hell.

This will be most people’s train of thought. It is not obvious that the conclusion it reaches is correct.

The Safety Dividend

Beyond changing how we allocate our attention and where we choose to live, driving automation offers a third critical benefit: dramatically improved safety. Automated driving will be such a massive improvement on the status quo that even if that attention was not being freed, it would still be a net good.

As we all know, human attention is not well suited to driving. Since the dawn of automobility, we have driven when tired; or angry; or drunk; or high; or distracted. The latter item is the scourge of our age. In the United States, the fatality rate for traffic incidents had been plunging for decades, but began rising again around 2014; not coincidentally, when smartphone penetration reached a majority of the population. In 2022, about 8% of road-related deaths were from distracted driving; and those incidents are just the ones where the driver admits to being distracted. The true percentage is presumably much higher than this.

Whatever faults they might have as drivers, computers are free of this one. They don't get bored. Nor do they drowse, eat, listen to podcasts, nor in any other way fail to attend to the driving task. A properly designed automated system has what we might call an unlimited attention span for the specific task it's designed to undertake.

Early results are promising. It’s not news, but worth underscoring that Swiss Re’s investigation of Waymo’s robotaxis found them to have dramatically better safety records than human drivers: 81% fewer crashes that deployed airbags, 78% fewer crashes causing injuries, and 62% fewer crashes reported to police, compared to human drivers in similar conditions.

The toll of deaths and injuries on our roads only fails to shock us because we are inured to it. If driving automation can indeed make roads significantly safer, it will make the other costs it imposes worthwhile.

Attention Must Be Paid

Driving automation will liberate human attention. In the fullness of time, it will give humanity back billions of hours each day, and we can expect that it will dramatically reduce injury and death on the roads. All these benefits are worth seizing, even as we see the potential drawbacks.

We have an opportunity to be thoughtful about this transition. Rather than letting it unfold haphazardly, we can choose how this attention dividend can be distributed and used; and to implement policy that will sharpen, or blunt, its effects. A vehicle-miles-travelled charge, for instance, could dramatically inhibit driving automation’s potential for sprawl; other possibilities exist.

We would be wise to begin considering them now. The End of Driving aims to help its readers to do just this.

Respect to Jeff Fong, Rob L'Heureux, and Grant Mulligan for feedback on earlier drafts.

Statistics for Canadians are hard to track down, but are presumably much the same.

None but the dustiest still call remote work teleworking.

At least at first. If there are any aspiring science-fiction authors in the audience, here’s a writing prompt for you!

I appreciate your exploration of the big questions here!

Regarding future changes in commuting time/distance, I'm curious how much we can learn from the difference between cities where commuter rail is available and convenient vs not.

I agree that people might be OK spending somewhat more time commuting if they don't have to drive, but I think the difference in satisfaction between commuting and actually having more free time is still much larger. Even if you can nap on the train, or in your self-driving car, waking up even earlier to go a further distance is still an annoyance I would argue that most people would rather avoid. So I'd be surprised to see average commute times get anywhere close to doubling in the future.

Perhaps you've thought about this before, but I think a more interesting implication of self-driving cars is the ability to do overnight roadtrips. Destinations that are ~8 hours away from major metros by driving could become more popular, and I could see some specialized vehicles and services emerging for this sometime in the 2030s that might convert some city-dwellers into non-car owners.

It would be interesting if we had better data on how the option to take the train changes peoples' sensitivity to commute times. Are we willing to trade an extra 15 minutes for a commute where you can read/write emails/watch videos? 30 minutes?

Of course there are mediating variables, but this would give us a much better sense of what will happen to our cities when AVs are adopted en masse. My guess is that people will accept somewhat longer trips--but I don't think it'll make hour long commutes attractive. Time spent watching a movie as your car drives you is still time you're not with your kids, or on your couch, or walking your dog.