Last month, Amtrak CEO Stephen Gardner resigned.

As per his statement, he did this “to ensure that Amtrak continues to enjoy the full faith and confidence of this administration”. Amtrak declined to confirm whether the Trump administration had asked for his resignation; but the White House itself confirmed that, yes, Gardner had been asked to step down.

Why? Asking for reasons from this government seems like a fool’s errand. Perhaps it was because Amtrak wasn’t doing a good enough job keeping homelessness and criminality out of Washington’s Union Station, as the Transportation Secretary suggested. Perhaps it was because of the administration’s frustration with executive compensation, as the Washington Post reported. Perhaps it was because train travel is now coded as Democratic, while roads and bridges are coded as Republican; I for one will never forget George Will’s dark mutterings that “the real reason for progressives' passion for trains is their goal of diminishing Americans' individualism in order to make them more amenable to collectivism”.

There’s no certain answer, but if I had to bet, I’d put money on Gardner’s downfall being the agency’s white paper explaining why it shouldn’t be privatized. The agency published it on 5 March 2025, and Gardner was gone two weeks later. Correlation does not mean causation… but when an agency pushes back against political direction and the next thing that happens is the CEO is asked to resign, it certainly suggests causation.

Was there political direction that Amtrak should prepare to be privatized? Of a sort. Elon Musk, the shadow president, said last month that Amtrak’s service was “sad”. He went on to say that “I think logically we should privatize anything that can reasonably be privatized… I think we should privatize the Post Office and Amtrak for example....We should privatize everything we possibly can.”

In this case (as in so many others), Musk is mistaken. Amtrak should not be privatized.

Amtrak absolutely has problems. As Alon Levy pungently observed recently, “Amtrak is best described as a mishmash of the worst features of every European and East Asian railway: speed, fares, frequency, reliability, coverage. Each country that I know of misses on at least one of these aspects… Amtrak misses on all of those, at once”. Amtrak certainly needs to up its game, and there is a path forward to do so. But before we get into that, let’s review the case for privatization, and see why it doesn’t hold up.

The Case for Privatization

The first point that privatization advocates make is a fair one: Amtrak’s service is terrible.

Most Amtrak routes, and particularly those outside the northeast, are slower than intercity buses. The Sunset Limited between New Orleans and Los Angeles, for instance, averages just 40 mph to 50 mph; adding insult to injury, it runs only three times weekly. On-time performance has been chronically poor; in some years, less than half of Amtrak’s long-distance trains have arrived on schedule. Equipment is dated; infrastructure is in poor repair, necessitating slow orders for safe operation (making service worse); and service expansion has been minimal, even as the country’s population has grown. The agency’s long-distance routes typically have a farebox-recovery ratio of only 49%, meaning more than half their costs were subsidized. Historically, about 15% of Amtrak’s riders (the long-distance passengers) have accounted for around 80% of the agency’s operating losses.1

The solution to this, some say, is to privatize the service. Look, for example, to Paul Weinstein Jr. in Forbes, who says that the private sector could potentially "dramatically improve service, infrastructure, and the ridership experience".

The financial case for privatization seems straightforward. Musk hasn’t given a rationale for Amtrak privatization, but as head of DOGE, he seems to have a jaundiced view of any government spending, and Amtrak is responsible for a great deal of it: Amtrak has required ongoing federal subsidies since its creation in 1971. Since that time, U.S. taxpayers have provided roughly $50 billion in support, with annual losses typically running in the hundreds of millions. If Amtrak were private, the burden of these costs would not fall on the public purse, and market discipline would reduce them in any case.

And then there’s the international angle. Rail privatization has been tried abroad. The breakup of Japan National Railways into private regional companies is generally regarded as a success story, with private successors like JR East offering good service while operating at a profit. And the introduction of competition on certain routes has driven fare decreases and service improvements in some European countries, like Italy and Spain.

And there are positive examples on this side of the Atlantic. Consider Florida's Brightline, which launched service between Miami and West Palm Beach in 2018; has extended service to Orlando; and now carries more than 2 million passengers annually, with expansion to Tampa planned. Its new venture, Brightline West, now aims to build high-speed rail from Las Vegas to the Los Angeles area. This 218-mile, $12 billion project is expected to be completed in 2028 with trains capable of 200 mph operation. If delivered as planned, Brightline West would cost about $55 million per mile; as Ryan Puzycki notes, that’s about four times less than California's troubled high-speed rail project. Brightline's comparative success suggests that private enterprise might handle passenger rail more efficiently than government agencies.

At first glance, this is a compelling case. If private enterprise can deliver better rail service without cost to taxpayers, shouldn’t it be permitted to?

If that was the question, the answer would obviously be yes. Unfortunately, matters aren’t so simple. Amtrak has its problems, but they are downstream of two fundamental issues. Firstly, Amtrak doesn’t have exclusive use of its track, and secondly, Amtrak has a mandate to provide service that doesn’t make sense. Under conditions like these, no actor, public nor private, could succeed, but stipulating them, a public actor has the best chance.

Amtrak’s Impossible Problems

The most critical obstacle to effective passenger rail in America is infrastructure ownership. Unlike countries with successful passenger rail, Amtrak owns only 3% of the route-miles it operates on.2 The remaining 97% are owned by freight railroads. Naturally, these outfits prioritize their own operations.3 Freight railroads have little incentive to prioritize Amtrak service, which generates minimal revenue for them, over their core freight business.

This means that wherever Amtrak train trips conflict with freight-train trips, the Amtrak train has to wait, which severely punishes Amtrak’s on-time performance. I mentioned earlier how excluding the NEC, Amtrak’s only achieves 45%-to-50% on-time performance. But why exclude the NEC? Because in that region, Amtrak owns approximately 80% of the rail infrastructure on which it operates (yes, that 3% of its owned trackage is massively concentrated in a single right-of-way). In the NEC, Amtrak achieves 75%-to-85% on-time performance. That number is still far lower than it should be, but the stark difference illustrates how important controlling track access is to on-time performance.

As further evidence, consider Amtrak service in Michigan. Prior to the acquisition of certain track segments, service on the Wolverine route between Chicago and Detroit suffered from poor reliability and lengthy travel times. Trains were frequently delayed by freight traffic, and average speeds hovered around 50 mph on a route with significant passenger demand. Fortunately for Amtrak, the State of Michigan purchased 135 miles of track from Norfolk Southern in 2013 to supplement the 95 miles Amtrak already owned. Thanks to having ownership over the track, the agency upgraded the Chicago-Detroit line to operate at 110 mph, with the result that travel times decreased, reliability improved, and ridership grew. When Amtrak controls its infrastructure, it can deliver better service.

So, in some areas at least, Amtrak controls its own trackage and can run good service; broadly speaking, that’s the NEC, plus some around Chicago and in California. And these parts of the system make money; the NEC consistently generates an operating surplus ($524 million in FY2018). Before the pandemic, Amtrak’s overall farebox recovery ratio got as high as 94.9%, and services in the NEC itself had a stunning farebox recovery ratio of 166%, the highest I have ever heard of in rail. While the agency as a whole still ran operating losses then ($168 million in FY2018), that was its lowest loss since the agency’s founding.

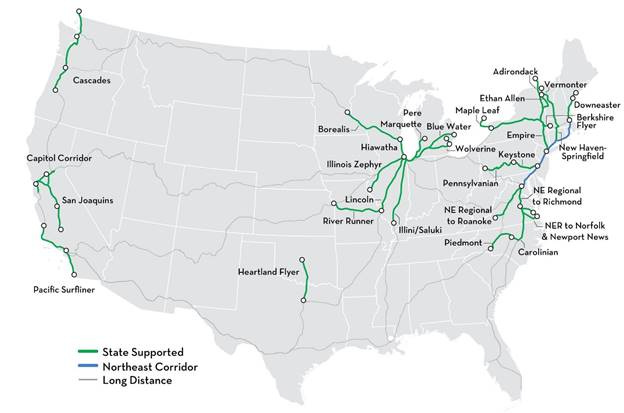

If the NEC made so much money, how did Amtrak as a whole come out in the red? Because it runs all sorts of service it shouldn’t. Consider this map, courtesy of Reddit:

Amtrak service as of 2024, courtesy of Reddit.

The NEC is in blue. Routes where host states support service with operating-cost offsets are in green. What’s hard to see is the long-distance routes in grey, which run down from the NEC into Florida, and criss-cross the country in parallel east-west bands. These are the routes that kill Amtrak: they’re incredibly expensive to operate and have little demand, because at those distances patrons prefer to fly. And yet Amtrak is obliged, by government mandate, to serve these routes.

That’s Amtrak’s problem, in a word: it must provide service on track it doesn’t own for which there is little demand, and because it doesn’t own that track, its service is poor, making demand even worse.

Privatization Won’t Solve Them

Given the problems, we can see that privatization won’t solve them.

Privatizing Amtrak would not grant Amtrak any more track than it currently has. Instead, privatization would make the problem worse. The new operator would still need to negotiate with the freight railroads for track access, but would presumably not have the benefit of federal regulations that are supposed to give passenger operations preference. Those regulations have been honoured mostly in the breach, but there’s no reason to think that a private firm would have any such preference at all; what would be the rationale for privileging any one rail user over another, if none are public agencies?

Nor would privatizing Amtrak help its successor coordinate with other rail users in its corridors, which is the primary reason that Alon Levy says NEC privatization is doomed to failure. Outside of Amtrak, the NEC trackage hosts more than 2,200 daily trains; not only Amtrak service, but also commuter services like MBTA, Metro-North, LIRR, NJ Transit, SEPTA, and MARC. Just as elsewhere Amtrak needs permission to operate from freight railroads, in the NEC these public-transit agencies need permission from Amtrak to use their trackage.

Right now, Amtrak and these transit agencies maintain a complex but functional relationship. While there are tensions—for instance, it’s alleged that Metro-North slows down Amtrak for its own dispatching convenience—these relationships are still more cooperative than those with freight railroads because all parties are public entities with shared public-service goals (but see this footnote added post-publication).4

A privatized Amtrak would fundamentally alter this dynamic. As the owner of the NEC rail infrastructure, a private Amtrak successor would have strong financial incentives to extract maximum revenue from the commuter railroads using its tracks. This might come through higher access fees or by prioritizing its own (likely more profitable) trains over commuter operations. The private operator would behave just as freight railroads currently do toward Amtrak: placing its commercial interests first, at the expense of the efficiency of the broader system.

Within the current structure, when coordination problems arise between Amtrak and commuter agencies, elected officials can intervene, bringing multiple public entities to the table to find solutions. This political accountability creates pathways to resolve disputes. A private operator would be accountable primarily to shareholders, making it less responsive to public pressure or political intervention when conflicts arise. This would likely degrade service for the millions of daily commuters who depend on these rail networks.

At this point, we might expect privatization advocates to return to the example of successful private operation in Europe and Asia. If it worked there, why wouldn’t it work in the USA?

The answer, of course, is that the USA is different: here, the rail network has been optimized for freight, and has been for more than a century. In Europe and Asia, it’s the opposite, and passenger service is prioritized, not only in policy, but also in infrastructure. The United States moves 40% of its freight by rail (versus about 8% in Europe), making American railroads the most efficient freight-railroad system in the world. It’s a great achievement, but one that has come at the expense of passenger service.

The idea that freight and passenger service can effectively share the same infrastructure at international standards of quality has been thoroughly disproven.

When passenger trains operate on freight-oriented infrastructure, they inevitably face substantial challenges that fundamentally compromise service quality. The tracks themselves are designed for heavy freight, with curve geometries and gradients optimized for fuel efficiency with heavy loads rather than maintaining high passenger speeds. One consequence of this are speed restrictions throughout the network, capping performance well below what modern passenger trains are capable of achieving.

Further, the physical infrastructure itself is maintained to freight standards, which permit rougher rides and different tolerances than passenger-optimized track. This creates a less comfortable passenger experience and places restrictions on the types of passenger equipment that can operate effectively. Additionally, to save maintenance costs, freight railroads have reduced capacity over time by removing double tracks, leaving fewer opportunities for trains to pass each other and limiting the frequency of service that can be offered.

These factors combine to create a fundamental mismatch between what passenger service requires and what freight-oriented infrastructure can provide. Passenger trains need straight tracks for speed, frequent service for convenience, and precise dispatching for reliability. None of these are compatible with America's freight network priorities.

The fact that European rail is optimized for passenger movement helps to explain why privatization has had some success there, though not as much as it may seem. European privatization has typically split operations from infrastructure, such that national agencies maintain the track while private operators run the trains. As night follows day, this incentive structure has led to private operators competing within the constraints of existing lines, without any corresponding incentive on the part of the state to extend or improve those lines. Competitive energy is spent on marketing, airline-style pricing systems, and rolling stock improvements; not bad things, certainly, but with diminishing returns to building out the network.

And I have to note the sour joke that privatization advocates point to countries like Spain, Italy, and France for evidence on the model's advantages, rather than to the UK, a place that publishes its data in English, making it easy for Americans to parse. It's not hard to see why; the UK's attempt to privatize rail in the 1990s had terrible results and is now being undone. The experiment led to higher fares, service deterioration, and safety issues. Three fatal accidents in the early 2000s were attributed to the neglect of the private infrastructure owner, which had become financially insolvent. After years of franchisees underbidding for contracts and then abandoning agreements, the UK has now reversed course, essentially renationalizing its rail system with the creation of Great British Rail to replace private train operators. Government subsidies for rail actually increased dramatically during the privatization period, contrary to promises of reduced public spending.

Amtrak has two fundamental problems. Neither of them is inefficient operation, the sort that private-sector discipline can fix. Instead, its first difficulty is a structural disadvantage in track ownership and control, meaning it can’t run good service in many places. Privatization would do nothing to solve this issue, and by fracturing the system further, might actually make it worse.

Amtrak’s second difficulty is that, as a public agency, it has a public mandate to offer expensive, near-univeral coverage that it is ill-equipped to provide. Here, privatization might help; if Amtrak was private, it could shed this burden.

But why go that far? Why not keep Amtrak public, and take that burden away?

The Better Way

Amtrak can succeed, but only if it focuses its resources on corridors where passenger rail can genuinely succeed, and where it can own the infrastructure on which it operates.

Pursuing this strategy means abandoning the politically expedient, but operationally flawed, model of providing minimal service across a sprawling national network. Matt Yglesias puts it more succinctly: “please stop being so stupid”.

The Northeast Corridor proves that passenger rail can work in America, but only when conditions are right. The NEC serves a dense population corridor in a near-straight line—ideal geography for rail service. Further, in the NEC Amtrak owns almost all of the rail infrastructure on which it needs to operate. Those conditions translate directly into performance. The NEC carries nearly 12.5 million riders annually (38% of Amtrak's total passengers), generates an operating profit, and achieves the highest speeds in the American system. Even with aging infrastructure that limits Acela to 150 mph maximum speeds, NEC service draws passengers from both cars and planes. This success comes despite infrastructure limitations that keep average speeds well below international standards.

As such, it seems clear that passenger rail in America faces a binary choice: either operate on tracks where the service has priority, or accept permanent mediocrity.

I say it should be the former. Rather than maintaining minimal service across a vast network primarily to secure political support, Amtrak should, as Matt Yglesias has written, adopt a corridor-focused strategy based on three principles.

Firstly, Amtrak must concentrate resources where success is possible. This means prioritizing corridors where population density can support frequent service and where public ownership of rail infrastructure is feasible. The NEC is the obvious starting point. Other corridors show promise, but only with sufficient investment, and with insistence on securing ownership changes. Beyond the NEC, promising corridors might include Chicago-Detroit, where as noted Michigan has already purchased significant trackage; and the Los Angeles-San Diego ‘Pacific Surfliner’ corridor.

Secondly, Amtrak should exit markets where excellence is unachievable. If infrastructure ownership cannot be secured and likely ridership doesn't justify the massive investment required, Amtrak should withdraw rather than providing substandard service that satisfies neither passengers nor taxpayers. This will mean difficult conversations with Congress, but the only alternative is continuing to spend gigantic sums in order to please no one.

Thirdly, Amtrak should expand strategically, and only from positions of strength. Like any transport network, the advantage of rail is that additional lines add value exponentially rather than arithmetically (see Metcalfe’s Law). From the NEC, extensions derive additional value from connecting to the existing network. Extensions like Washington to Richmond (which Virginia is helping to facilitate) makes the entire NEC more attractive. Building from strength ensures that investments generate maximum value. This means accepting that while, one day, linking Chicago to New York might be a wise move, linking either to California may never make sense.

That’s because the United States' reliance on rail for freight movement is a national success story, moving goods efficiently while reducing highway congestion and pollution. Displacing freight onto trucks isn't obviously an environmental or economic improvement. While some freight could potentially move to marine transportation, rail freight will remain essential for inland areas.5 This means passenger rail, at the broadest level, should not aspire to nationwide coverage.

By focusing on the Northeast Corridor, securing infrastructure ownership in key corridors, and planning the network based on transportation utility rather than political coverage, Amtrak could finally deliver service that meets international standards. This approach would likely serve fewer communities but would serve them incomparably better, and critically can be done better by not privatizing the service.

Incidentally, that link goes to my new-favourite title for a government report: “Better Reporting, Planning, and Improved Financial Information Could Enhance Decision Making”. You don’t say…

Specifically, Amtrak owns 623 route miles of track out of 21,400 route miles on which it operates.

This analysis also applies to VIA Rail, incidentally, as VIA also owns only 3% of its route-mile trackage. It’s North American passenger railroading that has a problem.

An anonymous subscriber—whom I happen to know is expert in this regard—tells me that the claim that Metro North detains Amtrak unnecessarily is vile calumny, and in fact Amtrak trains exit MNR territory less behind schedule than when they entered.

The Jones Act delenda est.

On the one hand, yes these are some good points and privatization wouldn't solve Amtrak's big problems.

On the other hand, Amtrak has so many aggravatingly stupid and wasteful smaller problems - like paying a bunch of people to line people up in queues outside the platforms instead of just letting people walk onto the platforms - that I can't imagine a private company tolerating, that I can't help but dream of the idea.

I wrote here about some similar themes: https://substack.com/home/post/p-160158165?source=queue

I strongly agree with the idea of building from strength and concentrating investments where they are most helpful. It is mystifying why electrifying really short routes like the Hiawatha isn't more of a priority. I crunched the farebox recovery ratios and basically some of the short likes in the northeast are doing pretty well, including basically anything originating out of NYC or the metro NYC area (Empire Service). With battery electric EMUs being able to significantly reduce the amount of catenary that needs to be strung up that you could do two really specific interventions to make lines profitable:

1. Electrify enough of the Hiawatha/Empire Service/NEC to VA/Norfolk with electric power so that they can run battery-electric EMUs

2. Buy more battery-electric EMUs with more seats

3. Turn some of the loss leader routes into the black and generate more profit.

While the long distance routes are unhelpful I do wonder how far you could get with such a strategy, a lot of lines even with the post-covid damages to ridership are over 50-60% farebox recovery, new rolling stock that let you do faster service without increasing the speed of the rails (because the rolling stock accelerates faster) you'd be able to maybe add stops, abbreviate timetables, or run more trains daily.