Cowen, T. (2018). Stubborn Attachments: a vision for a society of free, prosperous, and responsible individuals. Stripe Press. Available from Amazon.com and Amazon.ca.

In recent months, both the Ontario government and the government of Canada announced plans to mail modest cheques to citizens: $200 and $250 per adult, respectively. These were not stimulus cheques nor relief cheques, but explicitly ‘rebates’, giving citizens money for no other reason than to give them money.1 These plans managed to be both too small and too big.

Too small, because the value of any individual cheque would not meaningfully affect anyone's life. Too big, because in aggregate, they would cost billions of dollars to provide; a small sum multiplied by the millions who would be entitled to a cheque becomes a vast one. Spending that much would preclude significant investment in infrastructure, education, the military, or other matters of public interest.2

Tyler Cowen's Stubborn Attachments provides a powerful framework for condemning such policies: not because they are ineffective, but because they are morally wrong.

That claim may surprise you. It certainly surprised me; I am not used to economists arguing moral philosophy. Certainly Adam Smith did—his two most famous works are The Wealth of Nations and The Theory of Moral Sentiments—but that was centuries ago, and the two domains rarely overlap anymore. Generally, today I expect economists to support things they like, and oppose things they don’t, on the grounds of efficiency.

To pick a contemporary example, if your goal for your country is to make timber production great again, you could impose a tariff on timber imports, to encourage domestic production.

Here’s how I would expect an economist to respond. I imagine they might point out that:

Timber takes time to grow, so new production will take years to arrive, but in the intervening time every product that relies on timber will become more costly, depressing production and making everyone worse off

Available lands for forestry are already fully utilized, so either the supply of new timber will not increase… or it will, but at the expense of other things that might be better grown on that land, leading the country poorer on the whole

A thriving timber industry is both less valuable and less strategically useful than (say) a thriving automobile or software industry, because cars and software are both high-value products and useful in wartime.3 So if you want your country to be great again, don’t focus on growing more timber… focus on importing more timber and exporting more cars and computer programs. That agenda would make the country wealthier and safer on the whole

Each of these arguments tries to show that the measure being proposed will either be counter-productive, or productive but at the expense of other goals, such that the result is a loss on net.

This is how I expect economists to argue. I do not expect them to argue that wanting to increase timber production at the expense of automobiles or software is immoral; that to want such a thing is wrong.

And yet that, after a fashion, is sort of what Tyler Cowen is arguing in Stubborn Attachments.

As I said, that surprised me, but what surprised me more was that I ended up agreeing with him.4

The Argument

Cowen's core argument is straightforward: we should maximize sustainable economic growth while respecting human rights. This is not an economic claim, but a philosophical one. Economic growth is to be pursued, not because it’s efficient, though it is; not because it will help a nation or community be more effective at defending itself or pursuing other goals, though it will; but because it is the right thing to do.

As Cowen puts it, “...believing in the overriding importance of sustained economic growth is more than philosophically tenable. Indeed, it may be philosophically imperative”. Later, he says “Policy should be more concerned with economic growth, properly specified, and policy discussion should pay less heed to other values. And yes, that means your favorite value gets downgraded too. No exceptions…”

Why is this the case? Cowen starts by noting that across history, economic growth has consistently delivered tremendous benefits: it has “alleviated human misery, improved human happiness and opportunity, and lengthened human lives”. Wealthier societies offer better medicines, greater personal autonomy, more fulfillment, and more sources of enjoyment.

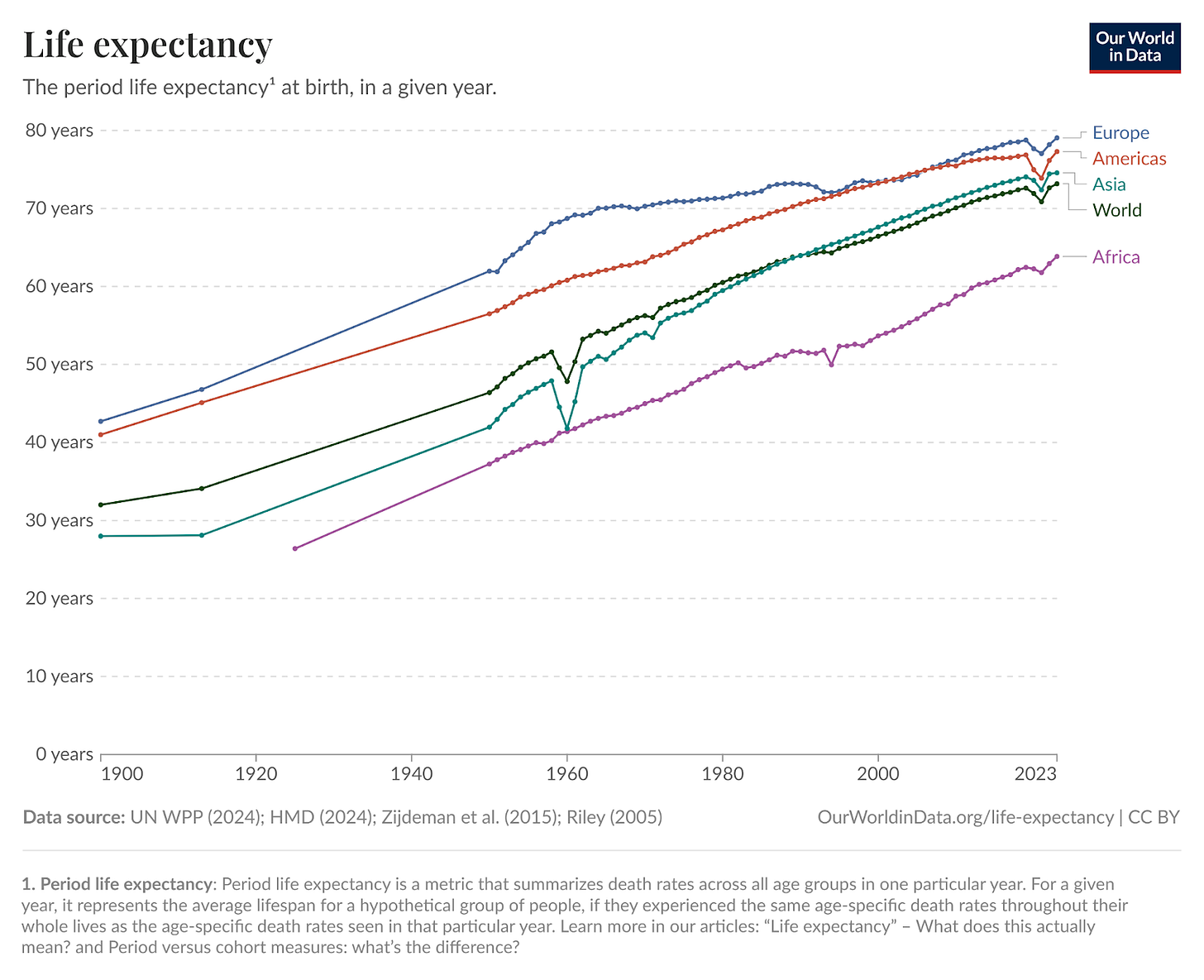

Consider how dramatically life has improved since 1900. Back then, life expectancy in Western Europe and the USA was around forty years. Nearly half of all U.S. households had more than one occupant per room. Only a quarter had running water. The high school graduation rate was just six percent. Most jobs were physically arduous with high rates of disability or death. Food took up half to three-quarters of a typical family budget.

Compare to today: life expectancy has roughly doubled in North America and Western Europe, to almost eighty years. Overcrowding is rare, with most homes having ample space. Running water and indoor plumbing are ubiquitous. High school graduation rates are above 85%, and a significant portion of the population pursues higher education. While some jobs remain physically demanding, many are now automated, and workplace safety regulations have drastically reduced rates of injury and death. Food costs consume a much smaller portion of the average budget, often less than 15%, even as the availability and variety of foods available has increased dramatically.

As Cowen notes, these improvements aren't just for the wealthy: for all of his wealth, Bill Gates's smartphone is no better than yours or mine. Cowen might have added that Gates drinks the same Coke and watches the same films that everyone else does; he doesn’t have access to Billionaire Coke or Billionaire Oppenheimer that are more delicious or thematically rich. And while he might have his own jet to fly from Seattle to Tokyo, Gates doesn’t spend less time in the air than someone flying commercially.5

Nor is the only comparison between Bill Gates and an average American; it’s between an average American and the average member of the global poor. Growth in wealthy countries benefits the latter through multiple channels: technological spillovers, remittances from immigrants, educational opportunities, and the spread of stable, well-aligned institutions, from the abstract—the rule of law—to the particular (name your favourite multi-national corporation). The Industrial Revolution began by making Britain wealthy, then Europe and North America, then the rest of the Americas and Asia, with China’s explosive growth happening largely in living memory. India and sub-Saharan Africa are next. The history of economic growth is, in large part, the history of poverty reduction.

Courtesy of Our World in Data: twentieth- and early-twenty-first century economic growth has made every part of the world, as a whole, better off

That’s why, says Cowen, economic growth is so valuable: it’s a free lunch, a way to generate ever-increasing value over time, without apparent end. Cowen uses the metaphor of a “Crusonia plant”, a plant that grows without inputs, but whose outputs of delicious food, and of more Crusonia plants, always increase. If you don’t like that metaphor, imagine a Philosopher’s Stone, or a genie who grants wishes… and who does permit wishing for more wishes. Cowen’s point is that pursuing a Crusonia plant or something like it will produce, over the long term, unlimited wealth.

Unlimited wealth would be valuable on strictly consequentialist grounds, but what makes it of paramount importance is that it can also help to resolve what philosophers call aggregation problems, or the difficulty of weighing different people's competing preferences. If there’s only one grapevine in the world, those who want wine and those who want jam can’t both be satisfied, and it will take great effort to determine who will get what they want, and who will be disappointed. If there are hundreds of grapevines, there’s the possibility of leaving everyone satisfied, or at least better off.

And so, Cowen argues, the right thing to do today is to choose neither jam nor wine, but seeds.6

Choosing seeds means that, in the future if not today, everyone’s preferences, whether for jam or wine, can be met. And not just with grapevines, but with all things. Even if some individuals might be better off with more jam-or-wine (consumption) and less seed (work and investment) today, if one includes in one’s choice a longer timeframe, the benefits of higher growth mean it will win any comparison.

To return to our earlier example, Cowen might agree with the economists making the case that tariffs on timber imports are inefficient. But he might further argue that their inefficiency means that the tariffs will lead only to rent-seeking by timber barons, and to less production and consumption in industries that rely on timber as an input. And that means that timber tariffs will lead to less economic growth, impoverishing the future relative to a policy of free trade. And such an impoverishment is morally indefensible.

And there we have it. Our fundamental moral obligation, in Cowen’s view, is to pursue policies that maximize the sustainable rate of economic growth.

Disarming the Critics

Cowen is prepared to be misunderstood, and spends most of his argument (in a very short book, only 160 pages) anticipating his critics’ arguments and rebutting them in advance.

Firstly, he uses an expansive definition of growth. When he uses this term, he means something far more comprehensive than GDP. He introduces the concept of “Wealth Plus”: a measure that includes not just economic output, but also health, leisure time, household production (valuable activities done at home for free), natural goods like national parks or clean drinking water, and other factors that contribute to human flourishing. Economic growth does not merely consist of expanding the production of traditional wealth, i.e., goods and services, but of Wealth Plus, i.e., goods, services, leisure time and household production, and the amenities of the natural world.

This expansion of the term’s meaning allows Cowen to address many common objections to growth-focused thinking:

So we should make everyone work 14-hour days to maximize measured GDP? No, because that would neglect the value of leisure time and the potential for burnout

So we should mine all the coal in open pits, burn it in furnaces to generate power, and leave the slag where it lies, to maximize measured GDP? No, that would make everyone worse off by scarring the landscape, intensifying global warming, and spreading black-lung disease

So we should condemn anyone who bakes their own bread rather than buying it from a bakery as irresponsible, or even evil? An industrial bakery is more efficient in both cost and scale than home production, and patronizing it will contribute more to long-term growth than baking at home. No, because while baking bread at home might be economically inefficient, it’s an exercise of enjoyable human capability, which is part of the good life

The reason long-term economic growth is good is because it enables more people to enjoy more health, more leisure, and a better pursuit of a good life. To pursue economic growth at the expense of those things would be perverse.

Secondly, Cowen insists that human rights must act as an absolute constraint on growth-maximizing policies. That word absolute is important, because if rights aren’t given this weight, they would be overwhelmed in any computation by the compounding benefits of economic growth; over a long enough time horizon, any rights violation could be justified by pointing to the accumulated benefits it would generate. For example, enslaving 1% of the population to boost economic growth by 0.1% per year could, in a purely utilitarian calculation, seem justifiable, if the time horizon was long enough. After enough years, the compounded benefits to the 99% would outweigh the suffering of the 1%, making the enslavement seem justifiable on consequentialist grounds. Cowen argues this kind of trading is morally repugnant. Negative rights—freedom from murder, torture, enslavement, political repression, and so forth—must be respected regardless of the potential economic benefits of violating them.7

Thirdly, Cowen emphasizes the "sustainable" part of "sustainable growth" by explicitly rejecting policies that might generate short-term growth at the expense of long-term stability. He points to the Shah of Iran as a cautionary tale; the Shah’s efforts to modernize Iran achieved high growth rates temporarily, but were so unpopular as to foment a revolution that ultimately proved destructive. We can see similar patterns in other countries that tried to grow too fast, like Stalin's Soviet Union, or Mao's China (during the Great Leap Forward), or—to pick a less extreme case—Brazil in the 1960s and early 1970s. In each case, the government, unconstrained by the need to respect rights, was able to sponsor remarkable growth… but at the cost of deep and widespread discontent, which eventually led to growth stalling out. Sustainable growth avoids these traps by ensuring that its benefits are spread widely, and so help to keep commitment to the project alive.

Fourthly and most radically, Cowen takes a firm stance on time preference. He argues that we should value future generations the same as present ones, rather than discounting their welfare because they are distant, or absent.

This is a breathtaking claim, economically and philosophically. A dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow to any lender; after all, the borrower might die, or forget, or find some way to evade his obligation, making the ‘future dollar’ actually worth zero. Even if the borrower makes good on the debt and returns that dollar, the lender has lost the returns he could have made in the meantime by investing it. Markets reflect this reality through interest rates: if you want someone to assume risk and delay consumption, you have to pay for that privilege.

Cowen argues this kind of discounting is morally indefensible when applied to human welfare across generations. He offers a thought experiment: imagine a healthy young 21-year-old living today, who discovers that he must shortly die of cancer. Imagine further that this is happening because, millennia earlier, Cleopatra wanted an extra helping of dessert, and took one, in full knowledge that it would cost some future person their life. Would we regard this as just? No, says Cowen, we would not. A human life should not be taken in return for an extra helping of dessert. That's true whether seconds elapse between the act and the reward, or centuries do.

The reason we have trouble seeing this, he argues, is that heavily discounting the future comes naturally to us. It’s an evolutionary hangover from our hunter-gatherer past, when long-term planning beyond immediate survival was rarely useful, or even possible. But this instinct leads us astray in our modern industrial civilization, with its persistent institutions and opportunities for compounding growth. We should overcome it, just as we strive to overcome other evolutionary instincts—from overindulgence in fatty foods to tribalism—that have outlived their usefulness.

Cowen has anticipated and addressed some objections to his argument. But challenges remain.

Objections and Contributions

Cowen's framework is obviously useful in straightforward cases, such as proposals to pay meagre ‘dividend’ cheques to taxpayers rather than investing in economic growth. But for more nuanced cases, its usefulness diminishes. Imagine a government has an unexpected $100M surplus. Should it expand higher education facilities, or lay the groundwork for a new nuclear reactor? Either could plausibly promote long-term growth, but not in quantifiable ways.

How then to decide? Cowen’s tools don’t offer a solution.

That alone is not disqualifying: as the kids say, hard cases are hard. But Cowen’s argument is even more of a difficult sell when, to buy it, we have to accept his position on the inadmissibility of moral discount rates. Cowen’s argument about Cleopatra, dessert, and dying young makes the case that it would be wrong for us to discount future welfare simply because it's distant in time. But the argument goes the opposite way too.

Just as Cowen offers a simple story of Cleopatra, let me offer a simple story of a medieval peasant. Imagine that this peasant could forego eating dinner to work longer in the fields, and if he does so, bread would, in our time, be a fraction of a cent cheaper. If we could speak to him from the future, should we tell him that if he doesn’t do it, he’s being selfish?

Surely not. If Cleopatra would have been wrong to harm her descendant for her own pleasure, it seems equally wrong to expect that peasant to suffer to benefit us, his descendants, who are far wealthier than he is. But we stand in the same relationship to our descendants as that peasant does to us… so why should we sacrifice for the benefit of future generations, who will presumably be wealthier than we are?

I suppose that Cowen would reply that it is bold of me to assume that future generations will indeed be wealthier than we are. That’s precisely what's at stake! Future prosperity isn't guaranteed. It depends on our choices today. Or perhaps Cowen would argue from sunk costs, saying that the past sacrificed to make us wealthy, but those sacrifices can’t be undone now; we can only benefit from them. And so we should ‘pay it forward’ by sacrificing something of our own bounty, to benefit the future… especially as it is such sacrifices that make prosperity possible at all. But these are only guesses, since the objection isn’t one that Cowen entertains.

Finally, Cowen’s list of caveats offers many ways to evade the force of his arguments. To return to the timber metaphor from earlier: a sophist might argue that an economy is growing ‘sustainably’ in Cowen’s terms if there are enough good jobs for workers who only have manual labor to offer; absent a domestic timber industry, there would not be enough good jobs; and therefore timber tariffs contribute to long-term growth, and as such are good.8 Similarly, the definition of 'Wealth Plus' justifies lots of current consumption as acceptable: examples might include baking bread at home, retaining large swathes of Alaska as natural preserves rather than drilling for oil there, and so forth. A clever sophist could argue on behalf of all sorts of selfishness as a form of 'Wealth Plus', as of a piece with other kinds of leisure. Ultimately, Cowen's philosophy is less of a hard-and-fast decision-making algorithm, and more of a low-and-slow tool for giving greater consideration to some proposals than others.

Image courtesy of Stripe Press

Notwithstanding this critique, however, Cowen ultimately won me over. The fact that his framework is better at ruling out bad policies than choosing among good ones is, for me, less a bug than a feature. As Cowen notes, much policy-making actively destroys value, by indulging short-term thinking and taking positions based on emotional resonance rather than careful analysis. In the world as we find it, a framework that helps us avoid obvious harms (like those $250 cheques) is useful, even if it doesn't answer every question.

The power of this approach becomes clearer when we consider how it differs from traditional consequentialist thinking. A utilitarian might support sending bonus cheques to citizens if they brought immediate happiness to enough people. Cowen's framework, by contrast, forces us to consider the compound effects over time: not just the immediate impact, but how those resources could have been invested to generate sustainable benefits for future generations.

Similarly, while the framework may not tell us exactly how to (say) split $100M between energy infrastructure and education, it does provide crucial guidance on the larger questions. We should focus on long-term rather than short-term returns, consider sustainability, respect rights while pursuing growth, maintain epistemic humility about specific implementations, and look for opportunities to create self-sustaining positive cycles.

If we accept it, Cowen’s argument has a striking implication: that many policies we take for granted, like governments running persistent operating deficits, or underinvesting in basic research, or failing to address climate change, are not merely imprudent but are also actively immoral. These policies rob the future, and harm future generations, for our own benefit.

That’s the real power of Stubborn Attachments: not in providing us with a skeleton key to unlock every policy problem, but in helping us recognize what is at stake in our policymaking, and indeed in many of our bigger life choices. It pushes us to consider longer time horizons, think carefully about sustainability and rights, and resist the temptation of short-term thinking. In an era where political incentives relentlessly push away from all of these things, it’s a worthy contribution.

Respect to

, , , and for comments on earlier drafts.I can’t prove it, but I suspect each government was inspired by the fact that in 2020 President Trump mailed out Covid relief cheques to Americans that had his signature on them, a move that President Obama later argued contributed to the outcome of the 2024 election.

Ontario’s cheques were mailed out. Canada’s cheques were not; before the plans could be finalized, the Finance Minister resigned in protest, a move that seems to have ended the Prime Minister’s tenure.

Well, cars are not so valuable during wartime, but tanks are, and the same factories can produce both.

You may wonder why I’m reviewing a book that came out in 2018. I’m doing it because it is new to me: attendees of the October 2024 Progress Conference each received complimentary books, and this was one of mine.

Though if Boom Supersonic keeps winning, that might change.

This is my metaphor, not Cowen’s.

Positive rights, to education or health care or other things, are already captured in his framework through the goal of maximizing sustainable growth, and as such don’t receive specific attention in this account.

Credit to Rob l’Heureux for making this argument, in a comment on an earlier draft.

The Cleopatra analogy bothers me because it misses a key reason to discount future impacts, which is that they're less certain. If you absolutely know for sure Cleopatra eating that cookie will give someone cancer you're assuming away the uncertainty of the future, which is kind of like assuming away entropy.

If that happens, it's out of the reasonable prediction window. There's no shortage of incremental improvements that are obvious now and extend into the foreseeable future. A person living 200 years ago would not have much of an idea about what your physical circumstances and aspirations are. If we apply the same logic in forward step of 200 years, I don't see that this is a question worth worrying about now. Someone else's with a wildly different perspective can make their decisions about what needs doing.