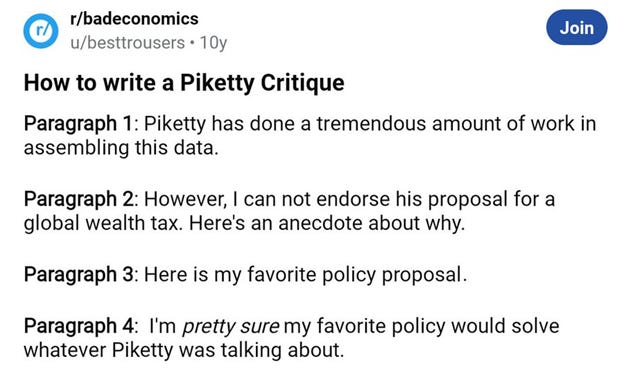

The public-policy book of ten years ago was Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Here’s a joke that went around at the time:

The joke’s author, Matt Darling, has noted that this is “the standard response to public policy books”, particularly in regard to the public-policy book of our moment: Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s Abundance.

The reason it’s the standard response is because most people have their preferred policies with which they are familiar, and it’s easier and more fun to talk about these things that they already know and care about than to engage with new, strange, and therefore difficult ideas.

With that in mind, let’s consider David Zipper's recent Bloomberg article, “What Would 'Transportation Abundance' Look Like?”

The abundance agenda, popularized by Klein and Thompson, argues that housing, health care, and energy are expensive because we don’t have enough of them; and we don’t have enough because we’ve established great barriers to building more supply; and we should rectify that by removing those barriers.

In response, Zipper follows the critique-of-Piketty playbook. He makes token obeisance to the idea of abundance, but as soon as he can, he drops the book’s arguments and picks up his favourite axe, namely Cars Are Terrible, and spends the rest of the piece grinding it.

It’s a shame, because in so doing, he mischaracterizes the abundance agenda, raises up straw men as opponents, and ultimately fails to see how an abundance approach could help actualize the sustainable transportation future he prefers. It’s a missed opportunity that we should rectify.

Blinded by Anti-Car Ideology

We’ve talked about this before, but a quick refresher: abundance advocates begin with a simple question. ‘Can we solve our problems in this sector with supply?’ The answer, more often than we would like to admit, is ‘yes, but…’

Yes, in that everyone would be better off if clean energy was cheaper, healthcare was readily available, housing was plentiful, and transport was fast, simple, and cheap.

But making them plentiful is functionally impossible. For a variety of reasons, we’ve spent decades creating procedural and regulatory barriers to increasing supply, such that it’s impossible to do. Accordingly, we have stopped trying, and our policy debates are instead about how to manage scarcity through regulation and redistribution.

In their book, Klein and Thompson identify four key sectors where scarcity has become particularly acute: housing, healthcare, energy, and transportation. In each area, they argue that a thicket of regulations, bureaucratic processes, and institutional inertia has constrained supply, driving up costs and limiting access. The abundance solution is simply to remove these barriers.

Zipper is on board when it comes to housing, healthcare and energy, but as soon as the abundance agenda enters his area of expertise, he gets twitchy.

Abundance has “intuitive” appeal for housing, energy, and healthcare, he writes, but “it is less obvious what abundance means for… transportation.”

Why is it less obvious? Because giving the people more of what they want means just that: giving the people more of what they want; not what he thinks they should want.

“…The vast majority of Americans travel by car,” writes Zipper, and so removing barriers to new transport infrastructure might mean removing barriers to building new roads, which "would threaten the planet, public health and urban life.” Thus abundance might be well and good in other areas, but in transportation, it requires “considering the kind of infrastructure that gets built, not just the quantity”.

For that reason, Zipper is happy that Klein and Thompson confine their explicit transport discussions to the USA’s inability to deliver rapid-transit projects like subways or California high-speed rail on time or on budget. For these, he’s in favour of removing bottlenecks. But not when it comes to highways: “State departments of transportations [sic] are infatuated with roadbuilding” and cheaper construction might simply encourage adding “lanes to already overbuilt highways”, which would be “counterproductive for climate and road safety goals”.

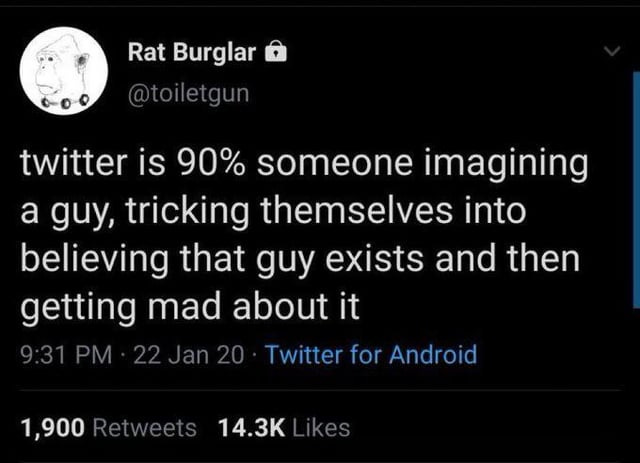

Is anyone arguing explicitly for making it easier to build highways? Well, no, but Zipper is afraid that someone, somewhere might do this. In the same fashion, he imagines “wolves in sheep’s clothing” that might start using abundance language to argue for eliminating fuel-economy standards, under the pretext of wanting “an abundance of personal transportation”.

To quote another Internet favourite:

Zipper now leans into his key point: “For abundance to be a useful framework for transportation policy… externalities must be taken into consideration”. He quotes Klein and Thompson’s vision of abundant transportation in 2050:

Electric cars and trucks glide down road [again, sic], quiet as a light breeze and mostly self-driving. Children and adult commuters follow on electric bikes and scooters, some personally owned and some belonging to subscription networks run by the city. Another last-mile delivery drone descends from canopy level, pauses over a neighbor’s yard like a hummingbird, and drops off a package.

My response is, where do I sign?

But Zipper is unmoved, arguing that this vision “jumbles together transportation technologies whose externalities are wildly divergent”. As far as he’s concerned, electric cars are good and e-bikes are great, but self-driving cars and drones are bad, because, in his view, the latter pose externalities for non-users.

(Of course neither drone delivery nor self-driving cars have yet arrived at scale, so it is not yet established whether they will impose externalities on users; or whether they certainly won’t; or whether they might, but won’t if we pursue good regulation. But never mind, Zipper’s on a roll, we’ll come back to it.)

Zipper emphasizes externalities as “enormously important” for understanding transportation challenges, explaining that every car trip “imposes societal costs” that aren't properly accounted for in American policy, effectively subsidizing cars and creating “a transportation system biased toward driving” that abundance could “further entrench.” His solution is what he calls “collective abundance” focused on “maximizing well-being for all”. In practice, this means removing barriers for things he likes, like housing and energy and high-speed rail, but not removing them for things he doesn’t, like auto infrastructure. Doing the latter “could be a prescription worse than the disease”. The goal should be “not just building more, but building smarter”.

As if anyone was suggesting otherwise.

A Paranoid Take on Highways

Zipper's analysis hits all the points in the lazy-critique-of-Piketty playbook. He acknowledges abundance's value, but rejects its application to transportation, and pivots to his preferred “collective abundance” framing, which is abundance, but only for things he likes.

There are two fundamental problems here.

Firstly, Zipper is so dismissive of cars, and of his fellow citizens for wanting to use them, that he presents a false choice between abundance principles and sustainable transportation.

Secondly, he is so engaged in the transport culture-war of our day, between transit and active transportation on one side and cars on the other, that he is opposed to the technologies of the future, on the spurious ground that they might support his opponents. That ground is spurious because it’s not at all obvious that future technology would support his opponents… but also because, even if it did, the result would still be a better world, by his own reckoning, than the one we have now.

Let’s take those in turn.

Zipper wrings his hands about abundance as applied to highway expansion because he is opposed to anything that might make such expansion easier. Abundance policy would make it easier to build highways, of course… but it would also make new rail lines or bike lanes easier to build too. The core abundance principle—making infrastructure cheaper and easier to build—is mode-neutral… or even slanted towards non-auto modes.

Let me unpack that. Would removing onerous engagement exercises benefit highway construction? Sure, to some extent. But it would benefit other modes far more. Our current regulatory environment doesn't slow all transportation projects equally.

Consider the challenges facing transit, bike, and transit-supportive housing projects:

The USA’s Federal Transit Administration requires extensive alternatives analysis, detailed cost-benefit studies, and local matching funds for capital grants. Environmental reviews for transit routinely take years. The result is transit projects that cost more, take longer, and face higher hurdles than comparable highway projects.

Bike lane projects face similar hurdles. And, at the local level, land use regulations compound these problems.

Minimum parking requirements force developments to dedicate substantial space to car storage, while minimum lot sizes and single-family zoning create distances too great for walking and transit.

In contrast to all this, the USA’s Federal Highway Administration distributes billions in formula funding to state DOTs with minimal restrictions and lots of exemptions.

The point is that these rules don’t have to be this way: they aren't the result of a first-principles thought process, nor the natural outcomes of the market. They are regulatory kludges that abundance principles would reform. And that reform would clean up a regulatory status quo that hurts transit without really hindering highways, boosting sustainable transportation far more than the automotive mode Zipper loves to hate.

Zipper doesn’t seem to understand this, which is why he has to imagine “collective abundance” as his solution. Unfortunately, it’s a solution to a problem that doesn't actually exist. The original abundance framework doesn't mandate building more of everything, regardless of consequences, as Zipper seems to imagine. Instead, it argues for removing unnecessary barriers to building what we actually need. If we did that, it would accelerate the sustainable alternatives Zipper favors.

A Boring Hack Job

Zipper presents transportation choices as binary trade-offs: highways versus transit, cars versus bikes, more versus less. And that’s because Zipper has chosen a side in a culture war. He’s in favour of transit, bikes, and walkable cities, and he opposes private cars and suburbs. And he’s so engaged in that conflict that he can only see innovation as a comfort to his enemies rather than an aid to his friends.

Electric vehicles (EVs) are one example. Zipper acknowledges EVs as “a clear upgrade over those running on gasoline,” but his praise is tepid, as if they're merely marginally better versions of the cars he detests. But they are much more than that; they're not only emissions-free, but also quieter, and cheaper to operate over the lifecycle. Because they run on motors, not engines, they can be smaller; there’s a market niche for small town-car EVs that could occupy far less space, and thereby address one of Zipper's core concerns about cars consuming urban real estate. Yet Zipper can't bring himself to explore these possibilities, because doing so might encourage people not to adopt his preferred transportation modes.

Or take drones, which receive similarly dismissive treatment from Zipper. He worries that “urban skies swarming with drones” would disturb “those who prize quiet and privacy”, as if noise and privacy concerns weren't readily addressable through thoughtful regulation. Worse, he misses that drones could reduce traffic congestion and harmful emissions, by handling last-mile deliveries that currently require gas-guzzling trucks to crawl through congested streets.

Yes, regarding freight, the externalities Zipper is so concerned about already exist: each delivery van creates noise, emissions, congestion, and safety hazards as it makes dozens of stops per day. Drones at scale would eliminate these externalities while providing faster, cheaper service, and paired with the right regulatory approach, would limit other bad outcomes. That’s a future that abundance thinking would conjure up more quickly.

But EVs and drones are sideshows. The real enemy is self-driving cars, for which Zipper has no use. He dismisses them out of hand, claiming their “net effect is highly contested” and suggesting they “could induce additional trips that cause a spike in emissions as well as crushing gridlock”.

As I have noted before, they certainly could. And, absent appropriate regulation and policy, it’s more than possible. (For what appropriate regulation and policy might look like, read The End of Driving, coming this August!) But just like with drones, it is a strange thing that Zipper prefers to ban a useful technology rather than regulate it appropriately.

It’s a shame Zipper is so fearful, because his fear blinds him to the ways that driving automation supports Zipper's own vision for transportation.

Consider parking. One of the biggest challenges for walkable urbanism is the enormous amount of land devoted to storing idle vehicles. Robust robotaxi networks—again, if properly regulated—could dramatically reduce or eliminate this need; when they aren’t serving customers, they can circulate, or better yet return to peripheral depots. Some space currently devoted to parking could be reclaimed for housing, businesses, parks, or, especially, the bike lanes Zipper adores (and which I, as a cyclist myself, adore also).

And as I have written at length, driving automation has extraordinary potential to improve public transit. It can help to solve the first/last mile problem by replacing infrequent feeder buses with prompt and direct connections to subway and commuter rail stations, and thus extending the effective reach of transit networks. Further, buses themselves could be automated, allowing for cheaper service, and thus service expansion, along busy corridors. Driving automation doesn’t have to compete with transit, it can (indeed, will) complement it, making car-free living more practical for more people.

And that’s leaving aside the elderly and disabled individuals who struggle with traditional transit and are ill-served by expensive paratransit today. Driving automation will provide them with better mobility and a lower cost.

Zipper can't see any of these possibilities, because he's trapped in a zero-sum mentality where any advancement in automobile technology must necessarily be bad for the modes, and vision of life, he happens to prefer. It's the transportation equivalent of the lump-of-labour fallacy; he seems to assume that there's only so much mobility to go around, and so making some modes better will necessarily rob and cheat the others.

By viewing transportation growth and innovation through the lens of a zero-sum culture war, Zipper misses the opportunity to explore how abundance principles could help achieve the sustainable transportation future he desires. Our insistence on establishing procedural barriers to abundant supply of transport, of all forms, is making us all poorer, and slowing down the arrival of a future in which everyone, including transit users, cyclists, and pedestrians, will be better off. Abundance thinking can help us help them by removing barriers to building the infrastructure—both physical and regulatory—that such systems require.

It’s a shame that the country’s foremost transportation reporter can’t see that.