‘As Good as Ridehail’ Isn’t Good Enough (But It's Close)

Six principles for robotaxi regulation

Last October, I was in a hotel in Fort Lauderdale, attending the annual conference of the International Association of Transportation Regulators (IATR), when Hurricane Milton made landfall.

The city was spared Milton’s full force—we were at the very outer edge of the storm, suffering merely rain and tropical-storm force winds—but nonetheless the conference’s mood was as gloomy as the skies. A message from hotel management was slipped under my door, informing me that I should close my curtains and stay away from the windows. The hotel, which was pet-friendly, was filled with grim-faced Floridians from farther north in the state, who had taken refuge with their dogs and cats. And in the conference rooms, anxious attendees murmured to themselves about the risk and impact the storm might have.

I had been invited to the conference to give a keynote speech on AI and future mobility, but that was already a few days in the past when the hurricane hit.1 I had remained on hand, in spite of the weather, because I was keenly interested in a later session: the IATR was going to discuss its guiding principles for the regulation of robotaxis.

IATR is the association for taxi and ridehail regulators. Today taxis and ridehail vehicles have human drivers, but soon they will not, and it will be the members of IATR that have to decide how to respond. Aware of the significance of the problem, IATR has been working on robotaxi policy for years, and the October 2024 meeting was a chance to showcase them for the world.

Unfortunately, the weather meant that many robotaxi representatives who had intended to be on hand were unable to attend. That was a shame, as those firms had been active participants at previous conferences, bringing their vehicles and engaging deeply with the regulatory framework.

Nor was the weather the only event to blunt the effectiveness of the IATR session. The same day, across the country in Burbank, California, Tesla launched the Cybercab. The result was that, for anyone interested in robotaxis, analysis of Tesla’s moves was the only game in town for the next few weeks.

Between the disruptive weather, and Tesla’s attention-stealing launch event, the IATR principles received far less attention than they deserved. That’s a shame, because these principles represent the best collective thinking of the people who will actually implement robotaxi regulation across the United States (and beyond). That would be enough to make them important, but the fact that the big robotaxi firms also contributed to their development is crucial, as that means they represent a modus vivendi of the regulators and the regulated. So coming to grips with these principles is imperative for anyone who wants to understand what will happen with robotaxis over the next ten years.

So today, let’s examine IATR's framework, explore where they get it right, where they may be overly cautious, and what their principles tell us about the future of automated vehicle (AV) regulation.

The Six Principles

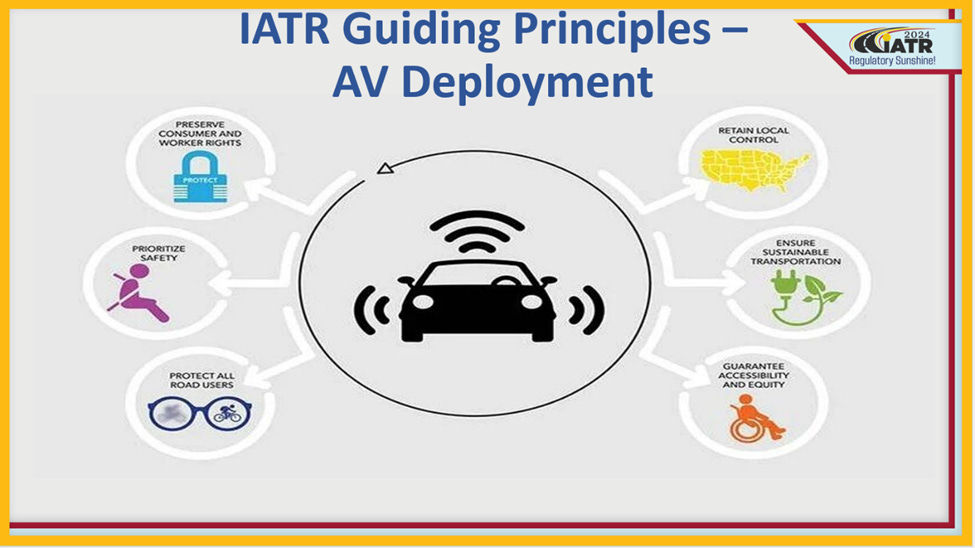

The framework consists of six principles, which the framework defines precisely.2 For brevity’s sake, I’ll rephrase them as follows, as the six things robotaxi regulation should aim for:

Operators Always Pay

Protect People, Not Jobs

Everyone Rides

Clean and Efficient

Vision Zero for Crashes

Local Guidance Yes, Local Veto No

Four of these principles are well-conceived and ready for implementation. The IATR has gotten it exactly right with Operators Always Pay: making operators fully liable protects the public while creating clear business expectations. So too with Protect People, Not Jobs, recognizing that natural attrition will ease the transition; Everyone Rides, mandating universal access as table stakes; and Clean and Efficient, requiring both zero emissions and congestion management.

The other two principles, while excellent starts, need more development. Vision Zero for Crashes is admirable but risks making the perfect the enemy of the good. And while Local Control correctly balances state and city authority, we'll need much more detailed frameworks to make it work in practice.

Image courtesy of the IATR

Let's examine each principle in detail to understand why.

Operators Always Pay

However safe and capable robotaxis are or will become, some road incidents are unavoidable. When they happen, IATR's principle on liability is ruthlessly simple: if a robotaxi causes harm, its operator pays. No exceptions, no confusion about responsibility, no passing the buck.

Global best practice is not yet defined, given how new robotaxis are. But if any principle has been established, this is it. Take, for instance, the UK's AV Bill, which introduces Authorized Self-Driving Entities (ASDEs). During automated operation, vehicle users bear no responsibility for collisions at all. Liability rests entirely with the ASDE.

This principle is easy to understand and to adjudicate, which are points in its favour. If one had to argue against it, one might argue it constitutes a regulatory moat. Today's robotaxi operators—Waymo backed by Google, Zoox by Amazon—can shoulder these costs through self-insurance or premium payments. But what about future entrants that don’t have a tech monopoly backing them? The insurance burden will be steep, particularly in early deployment phases when incident rates would, one imagines, be the highest they will ever be. Will the burden be so steep as to be prohibitive? So far it has not been, given Waymo’s ongoing success. But it is at least possible that insistence on full responsibility for their own products might fence out low-capitalized entrants from the market, and in the process deter innovation.

Still, I see no alternative: clear liability is the price of admission for automated vehicles on public roads. The public and their elected representatives simply won't accept automated vehicles on their streets without it, and nor should they. This insurance requirement is simply a cost of doing business that we will have to accept.

Some readers may be wondering at this point what I’m getting at. Surely if an AV is involved in an incident where it is at fault, of course the AV, as the party at fault, is liable; but if it isn’t at fault, then it shouldn’t be liable. Just what is at stake here?

The answer deserves a full post of its own, but briefly: an AV is a complicated product, consisting, at least, of software; sensors; and all the components of a traditional vehicle (chassis, tires, etc.). If there is an incident where the AV is at fault, there may be a great deal of investigation as to which element of the AV was responsible and where blame should lie. And such investigations should occur, but they are secondary to the AV company assuming liability for damages and making the injured parties whole. If the incident was ultimately the fault of a contractor or supplier, they can recover damages from those parties later; but that’s a separate matter from insisting, as a matter of principle, that if an AV is responsible for an incident, the AV company is liable.

I have to say, I wonder how this principle will work when (if?) the Tesla Cybercab hits the scene. As I understand it, Tesla owners will release their vehicles to Tesla, which in turn will use the vehicle as a robotaxi till the owner takes it back. I assume Tesla will be prepared to assume liability during that time? Surely it must, for no owner would surrender their vehicle to be used as a cab, knowing that if the software made a mistake they, the vehicle owner, could be held responsible. But Tesla’s behaviour has surprised me before… which is why I hope the IATR’s principle here is endorsed by governments, and regulation compels Tesla to assume this responsibility.

Protect People, Not Jobs

IATR's Worker and Consumer Rights principles aim to address both the immediate and long-term impacts of automation on the ride-for-hire workforce and its customers.

Regarding the former, IATR's view, which I share, is optimistic. Drawing on U.S. DOT analysis from 2021, they argue that widespread driving automation isn't going to kill the ridehail job market overnight. Instead, there will be a gradual transition where natural workforce turnover will absorb much of the impact.

The math makes sense. The ride-for-hire workforce is remarkably diverse: career taxi drivers, part-time ride-hail workers supplementing their income, recent immigrants using driving as an entry point into the workforce. Given this diversity, there is already high turnover in the sector: drivers retire, switch careers, or move on to other opportunities. As automation gradually expands, no one will be forced out, but as jobs churn, some will leave but they won’t be replaced. Meanwhile, new roles in AV production, maintenance, and monitoring will emerge.

The Teamsters Union has a different vision, pushing for federal protections: wage replacement, training programs, reskilling initiatives. For my part, I suspect natural attrition makes such programs unnecessary, but if they help us seize automation's benefits without unnecessary conflict, they might be worth the public investment. It's certainly preferable to the alternative the Teamsters also advocate: keeping human drivers in automated trucks.

On the consumer side, IATR embraces U.S. DOT's principles: safety, cybersecurity, and data privacy. These are, of course, unexceptionable, and rest on the understanding that public trust is imperative for robotaxis to succeed.

Everyone Rides

Existing workers and consumers are not the only ones affected by the rise of robotaxis; so too are the consumers whom the market should be serving but does not. IATR's Equity principle addresses this issue by insisting that robotaxis must not be restricted to the most-lucrative markets. They must also provide wheelchair-accessible vehicles that offer service to low-income areas with affordable fares. This insistence directly confronts the most difficult challenge in urban transportation: ensuring universal access.

Providing that access is a persistent challenge in American cities. Transit service to poorer and minority communities is limited or unavailable, meaning that ownership of private vehicles is high, despite how costly (directly and directly) that is. Access to taxis is limited, with few around to hail, and cabdrivers might simply choose not to stop if they didn’t like the looks of their potential fare. And those with mobility issues couldn’t expect any given cab to be able to accommodate them.

The advent of ride-hailing services helped; access by app made it easier to get access to a vehicle, irrespective of where you were or where you wanted to be picked up. Still, market forces have meant service concentrates in wealthy areas at peak times, making ridehail out of reach for many who would benefit from it. Wheelchair users continue to face challenges: while it’s possible to call an accessible vehicle now, there are few, and response times are long.

IATR sees robotaxis, like ridehail before it, as a tool to help make progress on the problem. Their framework expects operators to provide equitable access across all protected classes from the first day of deployment. This mandate to the private sector is combined with one to the public sector: the IATR calls for government subsidies to make automated service viable and available in areas that the market, on its own, might neglect. The Trenton MOVES project is an example of how this all might play out: a $100 million plan to deploy 50 robotaxi kiosks across Trenton, New Jersey, focusing particularly on areas of persistent poverty. Led by Princeton's Alain Kornhauser, it's an ambitious attempt to prove that automated vehicles can serve equity goals.

Let’s not pass over what this means: IATR is asking robotaxi companies to embrace costs that their predecessors, both traditional taxis and ride-hailing services, have worked hard to avoid. The economics might be more favorable for robotaxis, given their lower operating costs, but public subsidies will certainly be necessary, especially in less dense areas. That's a price worth paying if robotaxis can deliver on their promise of universal mobility access.3

Clean and Efficient

While equity is about ensuring good outcomes in the present, the IATR is also looking to ensure good outcomes in the future. The framework insists that robotaxis must "improve environmental outcomes through zero-emission fleets." This seems like pushing on an open door, given that Waymo and Zoox (and the late, lamented Cruise) have all-electric fleets and will continue to do so. Still, it’s good to make it explicit, given the tumult we should expect in the zero-emission vehicle market between now and 2035.

But electrification is the first word, not the last. The IATR also asserts that robotaxi firms should act to "reduce or mitigate congestion", by minimizing deadheading (i.e., trips with empty vehicles) and maximizing shared rides.

The IATR, having ample experience regulating human-driven ridehail, understands well the problem here. The cost of gasoline and of a driver’s time imposed some limits on the amount that human-driven taxis will circulate waiting for fares. Electric robotaxis, not so burdened, have great potential to impose severe congestion and environmental impacts, so I’m glad to see IATR foregrounding the need to think through appropriate rules to head them off now.

Vision Zero for Crashes

Up to this point, I’m on board with the IATR’s recommendations. Here is where we begin to part ways.

The IATR offers an uncompromising vision: robotaxis must "attempt to achieve levels of safety that exceed current taxi, TNC, and for-hire vehicle services." More provocatively, they argue that being "safer than a human driver" is "too amorphous" to serve as a meaningful standard. Instead, they want robotaxis held to Vision Zero goals: in other words, a standard that no road incident, much less loss of life is acceptable. Zero means zero.

Waymo likes to cite statistics showing their vehicles have fewer collisions per million miles than human drivers; half the rate we'd expect from human drivers. Some people I meet take from this an argument that Waymo itself, committed as it is to moving slowly and carefully, never makes. That argument is: if automated vehicles are safer than the status quo, why not make them street-legal everywhere today? Every set of trips that shifts from a personal vehicle to a Waymo would, on net, lead to fewer incidents, so why wait?

This just isn’t how regulators think, or least they have not behaved this way in my lifetime. Regulators aren’t concerned about the ‘balance of probabilities’ nor the ‘best outcomes on net’. They are concerned with ‘not being sued’. A regulator that approved the use of an automated vehicle on the roads that wasn’t taking all reasonable precautions to ensure the safety of other road users would absolutely get sued. Hence the high bar that robotaxis today must clear to be permitted to operate.

But it’s a bar that, at least in this present moment, robotaxis should be held to. Absent such insistence, one might expect a robotaxi company that behaves cavalierly—one in particular comes to mind—to introduce a vehicle that inflicts serious and unavoidable harm. That’s bad enough, but worse would be how such incidents would discredit the technology in the eyes of the public. It’s already the case that most people unfamiliar with robotaxis fear them; until that fear is quelled, IATR is correct to argue that robotaxis should take safety extremely seriously.

But, as worthy a goal as it is, we would do well to remember that Vision Zero has opportunity costs. Zero incidents is bold, and clear, and may win over skeptics, but it is so ambitious that it will slow deployment. And that too has its costs. The USA’s Nuclear Regulatory Commission has notoriously spent decades making it harder to build nuclear plants even as coal plants spewed megatons of pollution into the atmosphere. That wasn’t the NRC’s concern: its mandate was not to engage in cost-benefit analysis, but to ensure that nuclear power was held to the highest standard. In practice that meant they achieved Vision Zero on nuclear-related deaths… and Vision Tens of Thousands Dead from the burning of fossil fuels. I would hate for robotaxis to follow a similar path.

As such, I think in the present moment, the IATR’s proposed absolute safety standard is bold and worth endorsing, but as the technology matures and public familiarity increases, we will have to consider whether the bar should be lowered. Those people I meet, who think that since robotaxis are safer on net they should be deployed quickly? No regulator can afford to acknowledge it, but those people have a point.

Local Guidance Yes, Local Veto No

Finally, IATR's principle of Local Control addresses the question of who gets to regulate robotaxis. It’s a tricky matter, and IATR does the best they can with it. Their view is that federal and state governments should set safety standards, and cities must retain meaningful control over how robotaxis operate on their streets, including powers to designate operating zones and establish pickup points.

This is a live question because in 2023 and 2024, San Francisco and Los Angeles engaged in high-profile battles with California over robotaxi control. After several incidents of robotaxis interfering with emergency vehicles, San Francisco tried to restrict operations within city limits. The California Public Utilities Commission overruled them, asserting state-level authority. Los Angeles, watching this unfold, pushed for greater local control but was unable to change the state’s position. These conflicts foreshadow similar struggles in other states, demonstrating why we need clear frameworks: while cities have legitimate concerns about robotaxis operating on their streets, allowing each municipality to block deployment would create an unworkable patchwork of jurisdictions and deep uncertainty among firms. If any given mayoral or council election could result in withdrawal of permission to operate in an important market, the ability to grow and invest would be severely hampered.

IATR's solution is to offer each side something: states standardize safety rules and establish operating rights across the whole jurisdiction, while cities retain specific powers over where and how robotaxis can operate.4

This balance makes sense. Cities understand their streets best but shouldn't be able to simply ban robotaxis outright. Still, a city determined to make life difficult for robotaxis will find ways to do so through creative planning, as we’ve seen cities do for ridehail or shared scooters. So while IATR's vision is sound, implementing it will require crystal-clear divisions of authority between cities, states, and operators, along with a genuine commitment from all parties to make the system work.

A Foundation for the Future

IATR's timing was poetic. On the same day that Tesla unveiled its Cybercab, and their vision of a smooth, frictionless robotaxi future in the years ahead, transportation regulators in storm-threatened Florida were looking back, considering their results of years of work in making robotaxis work for everyone. It’s a metaphor for this present moment in the sector: a contrast between visions and promises on the one side, and the obstacles of implementation on the other.

IATR's framework shows us a path through that thicket of difficulties. Four of its principles—clear liability, workforce transition, universal access, and environmental responsibility—give us a solid foundation. They tell operators exactly what society expects of them, and they're achievable with today's technology and business models.

The remaining principles—safety standards and local control—point to the hard work ahead. We'll need to find the sweet spot between Vision Zero's admirable goals and the practical benefits of getting robotaxis on the road. We'll need to forge new relationships between cities and states, creating frameworks that give local authorities real ability to shape service in their domains, but without privileging the status quo at the expense of the future.

The IATR principles show us that at least some of the key players, both regulators and operators, are ready to do the hard work of making robotaxis serve the public well. That's worth paying attention to. And I agree with this emerging consensus among regulators and industry, that ‘as good as ridehail’ is setting the bar for robotaxis too low.

But let’s not let the perfect be the enemy of the good. Even one notch higher would be enough.

If you have a conference that you’d like me to speak at, or you’d like to see some clips of that talk, please visit my professional website and get in touch. Satisfaction guaranteed!

In order, the formal names are Prioritize Safety; Protect All Road Users; Retain Local Control; Preserve Consumer and Worker Rights; Guarantee Accessibility and Equity; and Ensure Sustainable Transportation.

This is also a topic that The End of Driving, and this newsletter, will discuss in detail this year. Here I should also add that, consistent with my views on transit, public subsidy should go to the users, not the firms.

I note in passing that IATR suggests that, in some cities, parts of the central business district should be closed to all cars except robotaxis, automated vehicles, and buses. That’s not on anyone’s agenda today, but in a few years, it may be possible, and I think would add a great deal to urban life. This is another topic that The End of Driving and this newsletter will consider this year.

Has IATR considered what to do in regional emergencies, like the people fleeing the hurricane you mentioned or more recently the fires in SoCal? It might be the last bastion of truly needing a car, but an unfortunately salient one for millions of people.