A.I. Hype, Transit Jobs for the Boys, and the Tesla Board's Dilemma

Off-Ramps for 13 February 2025

Welcome to Off-Ramps! Today I’ll highlight three interesting pieces that I think you will enjoy reading. Please enjoy these on your morning commute, or save them for your weekend.

(Normally, of course, I offer you four pieces, but about these three I have more to say than I often do.)

1. A.I. Is Today Where Driving Automation Was Ten Years Ago

Earlier this week, I announced the forthcoming publication of my book The End of Driving, co-written with Bern Grush and John Niles, coming later this year. This book is the second edition; the first edition came out in the summer of 2018.

A principal concern of the first edition was to defend against endless waves of hype. Bern and John were reacting to ‘futurists’ and ‘thought leaders’ who insisted that driving automation was about to change everything forever. Looking back now, such material seems so comic, it’s hard to remember how seriously such claims were taken back then.

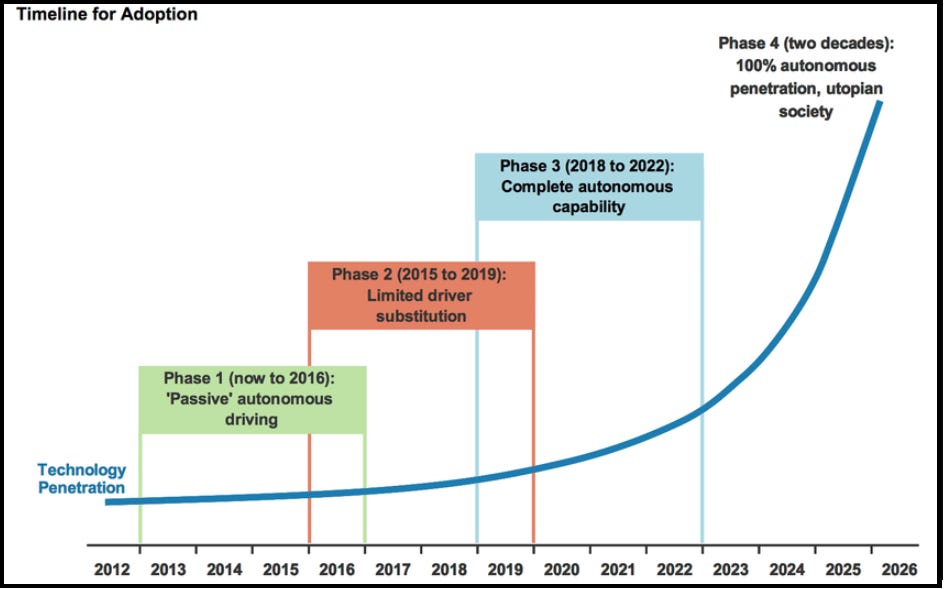

I can’t resist posting my favourite entry in the genre, courtesy of investment bank Morgan Stanley, circa 2015. I will provide no link, to protect the guilty:

What I like best about this prediction is not its claim that by today, in 2025, driving automation would have completely eliminated human driving. What I like best is the claim that, thanks to that elimination, we would also be living in a utopian society.

As we note in the book, one consequence of this irrational exuberance was it prompted its own backlash, a wave of irrational denunciation: that automated driving was just a scam and would never actually arrive. (Here is a good example of the genre.) Neither the hype nor the scorn was justified, but if you want to harvest clicks, simple and emotional stories work better than nuance. And the more you trade in outlandish hopes and dreams, the greater a market for outlandish condemnation. Waymo recognizes this, which is one reason that they avoid drawing attention to what they’re doing. Tesla goes the other way; more about that in a moment.

The reason I’m bringing all this up is to give context to a recent piece by friend of Changing Lanes, Tim Lee:

Lee makes the point that those who traded in scorn were wrong: robotaxis are and were not a scam, and were coming. Those who traded in hype were also wrong because they underestimated the speed at which driving-automation tech would arrive. What was always going to take decades, they thought would take a couple of years at most.

If you’re curious about why the rollout of driving automation is taking so long, and the technical, economic, and socio-political barriers it needs to overcome, you will want to read The End of Driving, available later this year. But while you wait, read Lee, who argues that where driving automation was in 2018, artificial intelligence (AI) is today.

Lee is absolutely right that the claims made for AI have become loud, thorough, and inescapable. Once people seem to be competing with each other to make the biggest claims (see this, for example) about how fast and thorough-going change will be, that’s the time to hold onto your wallets. Remember that that breathlessly-overexcited chart above was produced by an investment bank that wanted readers to give it their money. Presumably that would have been invested on the premise we’d have a self-driving utopia by next year; I wonder what the returns have been like.

Tim explains, accessibly, why the claims made for AI right now are as likely to be overblown as claims about driving automation were eight years ago. He writes “I just want to encourage people to remember that it’s very common for the pace of technological change—and the pace of adoption by the general public—to be slower than industry insiders expect.”

I agree.

2. The Purpose of a Transit Agency Is Not to Provide Jobs to Its Workers

Since the last presidential election,

has been slow-rolling a manifesto for the Democratic Party to regain power by embracing pragmatic centrism. One of the planks of that manifesto is the following claim: Public services and institutions like schools deserve adequate funding, and they must prioritize the interests of their users, not their workforce or abstract ideological projects.The whole thing is worth reading, though it is paywalled (sorry). I’m highlighting it here because the middle section is a story I hadn’t heard before that deserves wider currency. We might call it That Time Joe Biden Tried to Stop California from Automating Transit.

Well, not really. What Biden’s Labor Department did, back in 2021, was to deny California $12 billion in grants to California transit, on the grounds that Section 13(c) of the Urban Mass Transportation Act of 1964 requires that a transit agency receiving federal funds can’t ever do anything to make its workers worse off. In this particular case, the Labor Department alleged that California had done just this by reforming its public-sector pension system to restrict benefits to new hires. Crucially, California had done this in 2013; so eight years earlier.

In other words, Presidents Obama and Trump hadn’t had a problem with this pension reform. But the union hadn’t forgotten; and when Biden entered office, the California transit unions saw a chance to settle an old score, and they took it. And their weapon of choice was to deny their own employers $12 billion in relief funds (in the midst of a pandemic that had all-but-eliminated ridership and fare revenue). And Biden went along.

Ultimately, the state’s governor and its federal senators complained and the Labor Department reversed its decision. But the larger point was made: the federal government was at least open to using Section 13(c) to protect the interest of transit labour unions, over and against the interest of operators or riders.

That matters because the same law makes it all-but-impossible to automate transit operations. To be compliant with 13(c), a transit operator can only automate its operations if it waits until all workers who might become redundant to retire; or buy them out. Note that this doesn’t apply to new, wholly-automated service, because no existing worker will be harmed. But if a current service wants to optimize its offering, the interests of the workers come first.

This is ire-inducing. As I have argued, at length, progress in public transit requires automating everything we can. The point of a transit operator is not to guarantee work to its employees, but to provide the best service to its patrons it can afford. The Trump administration and its shadow president, Elon Musk, have declared that they aim to eliminate all regulations that choke growth and the future. I encourage them to take aim at this one.

3. More on the Musklash

Speaking of Musk: in the most-recent issue of Off-Ramps, I wrote about the “Musklash”. This was a backlash, still anticipated rather than real, against Musk, on the argument that he was acting out in a variety of ways that had the potential to alienate his key constituencies: conservative populists, Silcon Valley tech enthusiasts, and otherwise-disengaged fans of his brash public persona.

Today I’d like to put that argument into context by talking about Tesla Motors’ market capitalization.

It is difficult to overemphasize how gigantic Tesla’s market cap is.

Screenshot from Google, 12 February 2025

At time of writing, it was 1.05 trillion USD.

As I have written before, the human mind has trouble understanding figures that large. So here are some ways of expressing it that will make it clearer:

Tesla’s market cap is the largest of any carmaker in the world

Tesla’s market cap is 4.5 times the size of the next-biggest carmaker, Toyota

Tesla’s market cap is roughly the same size as the market cap of its 15 biggest competitors combined

Tesla’s market cap makes up 42% of the value of all the carmakers in the world

Put another way: there are not even ten companies in the world with a trillion-dollar valuation. Most of these are tech companies (Microsoft, Apple, Alphabet, Meta, NVIDIA); the others include Saudi Aramco, which sells oil, and Berkshire Hathaway, which is an investment firm.

So Tesla’s position here is anomalous, for two reasons. For one, it’s the only manufacturer.1 For another, it’s also much more valued than other firms in its sector, by a gigantic margin.

It’s not hard to see what’s going on here. Tesla’s stock value has less to do with the nature of its products, and more to do with the nature of its CEO. Tesla’s market cap broke into the trillion-dollar club on 6 November 2024, the day after Donald Trump was re-elected president.

In other words, investors are not looking at Tesla’s future value when they trade its stock; they’re looking at Elon Musk’s future value. They think his influence on the new administration is valuable, and they’re investing appropriately.

This is why I do not envy the people who sit on Tesla’s board. (Well, in many ways, I do envy them. To be clear: if a seat becomes open, I am available.) But I don’t envy them the decisions they’ll have to make.

That’s because Elon’s role in the Trump administration is having demonstrable effects on the Tesla brand. Courtesy of Reilly Brennan, I note that 6-in-10 Britons would rather buy a Chinese EV than a Tesla, explicitly because they have come to dislike Musk. And the effect is widespread: Dutch Tesla owners are considering selling their cars because of Musk’s behaviour. Similarly, as Trump’s tariffs threaten Canada, Toronto is poised to refuse subsidies to ridehail drivers with Tesla vehicles. As Musk and Trump alienate people abroad, and indeed at home, those people are striking back against Elon’s brands.

The problem for Tesla, as I see it, is Elon’s influence with the administration is the principal source of the firm’s value today; but that is temporary. The damage he is doing to the firm’s brand is permanent. So what will happen when Elon becomes the bad boyar, as seems inevitable? What should Tesla be doing now to prepare for that day?

That’s up to the board to decide. Good luck to them.

Apple is also a manufacturer of iPhones and other hardware, but its high value derives even more from its software assets, like the App Store, that Apple phones can access. Tesla’s value stems from its cars, and to some extent access to its charging network.